Lessons for Resilience

Consider creating voluntary sector-led 'wellbeing hubs' to reduce pressure on the health and social care system

Well-being hubs strategically placed across a location could build on successful initiatives already delivered by the voluntary sector. Such hubs can be used to tackle health inequalities, and help reduce the rise in mental health issues due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hubs would ideally offer face-to-face support, and would have to ensure COVID-19 safety measures. Hubs may support:

- Health services during the COVID-19 pandemic and relieve pressures on the system through partnership working between healthcare providers, local councils, housing and the voluntary sector e.g. The Hubs in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, relieve pressure on primary care - in six months The Hubs have seen almost 2,000 people including 636 urgent referrals

- Preventative health and wellbeing policies that protect people and reduce potential strains on health and social care services

- Social prescribing, whereby local agencies can refer people to a Link Worker who support people in focusing on 'what matters to me' and taking a holistic approach to health and wellbeing. They connect people to community groups and statutory services for practical and emotional support

-

United Kingdom

https://vcseleadershipgm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Building-Back-Better-in-GM.pdf

-

United Kingdom

https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/case-studies/nhs-and-social-care-hub-helps-people-at-risk-stay-well-and-out-of-hospital/

Consider how to support middle managers in creating supportive and healthy working environments during COVID-19

Middle managers and leaders are central points of contact for people returning to work and their roles are particularly important as the pandemic continues but people return to work. However, it is vital that managers have the tools to support their own well-being as well as their team's, and that they have adequate support from senior leadership. Since COVID, middle managers are being asked to make hundreds of daily decisions in a time of uncertainty. They have the responsibility of sharing and promoting decisions and strategies that may be ambiguous or that they even disagree with. Consider:

- Conversations between middle and senior leaders that helps to remove as many unknowns as possible through clear guidelines. Ensure managers know what they are (and are not) responsible for in terms of decision-making and providing wider support

- Whether there is sufficient wellbeing support for all staff to relieve middle managers of additional roles. Ensure managers are clear on available support networks in the organization and what they offer e.g. occupational health

- Provide training on holding 'confident conversations' about difficult topics e.g. mental health, risk assessments, managing people with different needs, and providing more emotional support

Train managers in available information such as the NHS’s: Making health and wellbeing vital in conversations guidance and wellbeing coaching questions - for managers. The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development's (CIPD) offers: How to help your team thrive at work

-

United States of America,

United Kingdom

https://www.nhsemployers.org/publications/staff-experience-adapting-and-innovating-during-covid-19

Consider Renewal through People: Reconciliation and Reparation

Implementing recovery

We argue that Reparation is only one step in the process of helping people recover and move forward from COVID-19. An approach which considers Reparation and Reconciliation is required to build trust, and encourage healing in, and between individuals, communities, organisations and levels of government.

Follow the source link below to TMB Issue 24 to read this briefing in full (p.2-12).

Consider that many people may be anxious about returning to workplaces and how effective support can be offered

Many people may be concerned about the rising cases in some areas and the risks of returning to work. So, the return to workplaces, including the risks this may pose to people’s health, may cause anxiety due to a heightened sense of risk of COVID-19 infection and uncertainty. Consider how new routines may be developed to avoid people becoming overwhelmed. Consider:

- Regular team meetings and debriefs to discuss anxieties about returning to work and any concerns or learning that may arise

- Allocating dedicated ‘buddies’ to support colleagues at work. These people could be from other departments to support confidentiality, and have specific training on helping people to manage their anxieties, on the organisations’ process and plans for safe working, and additional services staff may want to access

- Clear and simple protocols that outline how workplaces will keep employees safe and any workplace adaptations that have taken place

- Accessible ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ sections on organisations’ websites to provide answers to the most common concerns, including signposting to other relevant services such as health and wellbeing support at work

- Providing opportunities for e-learning or training on managing anxiety about returning to work and COVID-safe practices in the workplace

- Surveying staff to understand their enthusiasm for returning to work and addressing concerns raised

-

United Kingdom

https://www.cardinus.com/insights/covid-19-hs-response/anxiety-returning-to-work-post-covid-19

Consider how to continue to provide fun family events for children during COVID-19

Children have been particularly impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, so continuing to provide child-friendly events is an important way to safeguard their well-being. Consider how and what advice to provide to the public to make celebrations such as Halloween and Bonfire Night COVID-19 safe. Consider widely publicising the safety concerns of some activities such as trick or treating and firework parties, and provide ideas for low risk alternatives. Consider suggesting:

Halloween

- Virtual trick or treat parties or costume parties

- Carving or decorating pumpkins with members of your household and displaying them

- Having a scavenger trick-or-treat hunt with your household members in or around your home

- Look for community events focused on safe ways to have fun e.g. children can colour in Halloween posters and display them in a window at home so, on Halloween children can get dressed up and look for posters in their local area and get a treat from their guardian for each poster spotted - ensuring social distancing and 'the rule of six'

Bonfire night

- Instead of putting on fireworks displays, consider lighting up local landmarks at certain times. In Dudley, UK the council intends to honour NHS workers by also lighting up hospitals. The display is also accompanied by music played on local radio stations

- Consider secret firework displays which are planned at undisclosed locations to avoid crowds gathering - providing locations to ensure full area coverage

- Livestream displays on social media

- Heighten awareness of firework safety as COVID-19 restrictions may result in more firework displays at homes. Promote following the firework code and relevant COVID-19 restrictions

-

United Kingdom

https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/COVID-19/Pages/Halloween-COVID-Safety-Tips.aspx

-

United States of America

https://www.cheshirepolicealert.co.uk/da/344971/Halloween.html

-

United States of America

https://www.stourbridgenews.co.uk/news/18783282.free-bonfire-night-fireworks-display-promised-dudley/

Consider how to develop an easy-to-use website to disseminate information about local lockdowns

The COVID-19 pandemic has produced a huge amount of information from a variety of sources, not least on the rules for local lockdown. In the UK, COVID-19 rules vary depending on whether you live in England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. In addition, millions of people are also affected by local restrictions. In Greater Manchester, for example, these restrictions have differed between metropolitan boroughs. The BBC have created a webpage 'Local lockdown rules: Check Covid restrictions in your area' that provides an example of how to support the public in finding information about COVID-19 restrictions in their areas, or areas of interest, through postcode searches. This helps to provide information about restrictions in individuals' locations and that of their friends, family or workplaces.

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-54373904

Consider how to manage Remembrance Day gatherings

In the UK, war veterans attending Remembrance Sunday commemorating the deaths of those in the armed forces across the Commonwealth, will be exempt from new laws restricting gatherings. Many of these people are vulnerable to COVID-19 as a result of age or underlying health conditions which has meant many local councils cancelling parades and church services; urging people to pay their respects in other ways and at home this year. Consider:

- If parades take place in your area how to ensure:

- Rigorous risk assessments are carried out, including the enforcement of social distancing

- That the event does not draw much larger crowds, and what contingencies are in place if this happens

- That people, especially elderly and vulnerable veterans understand the risks posed to them by participating in a parade

- That PPE is provided for event organisers and participants

- If parades do not take place consider designating a period of a few weeks for people to pay their respects and lay wreaths at memorials, rather all on one day

- Live stream local events that include small select parties of individuals laying wreaths e.g. in Bradford where parades are cancelled, The Lord Mayor will lay a wreath at each memorial site across the district

- Encourage residents to pay their respects at home in different ways:

- By observing the national two-minute silence

- Displaying poppies or other symbols (posters, children’s drawings etc.) in home windows

- Using hashtags on social media such as #Bradfordremembers with pictures of acts of remembrance at home or school

-

United Kingdom

https://www.thetelegraphandargus.co.uk/news/18788077.covid-pandemic-leads-changes-remembrance-day-events/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/remembrance-sunday-veterans-coronavirus-ban-gathering-risk-areas-b996583.html

Consider how to promote conservation agriculture to mitigate the impacts of climate change

COVID-19 has resulted in food shortages in certain parts of the world due to disrupted supply chains. The compounding impacts of poor harvests as a result of climate change requires the adoption of new farming techniques to protect the environment and lives and livelihoods. Conservation agriculture promotes minimal soil disturbance, crop diversification and the use of organic fertilizer to conserve and improve the soil, and makes more efficient use of natural resources. It is therefore climate-smart from an adaptation as well as mitigation viewpoint. Consider:

- Introducing environmentally friendly legislation and incentives. In the UK, the Agriculture Bill is reforming farming to provide subsidies not simply for cultivating land (which is the current EU approach) but for delivering "public goods" e.g. sequestering carbon in trees or soil, enhancing habitat with pollinator-friendly flowers

- Moving beyond a model of short-term farming subsidies e.g. through stronger legislative commitments to long term funding, domestic environmental and animal welfare standards, and safeguards on import standards

- How to promote the benefits of conservation agriculture for farmers including financial savings that can be made due to less use of machinery, labour and pesticides

- Using digital technologies to disseminate important information on how to limit post-harvest losses, and improve better access markets and financial services

- Encouraging the public to continue to 'buy local' during the pandemic (e.g. through farms practicing conservation agriculture), as this supports local, sustainable food supply chains

Consider levelling up regional economic resilience: Policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis

Dr Marianne Sensier and Professor Fiona Devine, The University of Manchester, analyse economic resilience in UK regions and recommend additional policy measures to address the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19.

To read this briefing in full follow the source link below to TMB Issue 23 (p.2-6).

Consider the digital literacy of teachers, and their capacity to teach children effectively in an increasingly digitized world

Computers and other digital devices are increasingly being used to teach children, and as part of children's education into today's digital economy. However, research shows that technology's impact on student learning has remained limited, partly because the rapid adoption of technology has not been accompanied by appropriate training of teachers. COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of digital technologies. It is important that teachers have the capacity and capabilities to use emerging and new technologies, and to impart these skills onto students as they will be required to navigate and work in a digital world. Consider:

- How to develop partnerships between schools and the technology industry to help teachers develop the skills they need to educate children effectively

- How to offer and encourage teachers to undertake additional qualifications to support the curriculum e.g. Fujitsu's Certificate of Digital Excellence (CoDE) which is a free, online learning experience for teachers, which helps educate them on topics such as Artificial Intelligence, cyber Virtual Reality, Big Data and Programming and Robotics. Each of these has been recognised as a technology or skill needed by the next generation to help with their future careers

-

United Kingdom

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

Consider co-designing response and communication strategies with the public

Guest briefing by Dr. Su Anson and Dr. Katrina Petersen, Trilateral Research and Inspector Sue Swift, Lancashire Constabulary, prompts thinking on risk communication approaches in the context of COVID-19 and how the public can be active agents in their own response. The authors focus on: Identifying goals and outcomes; developing the message; channels for two-way engagement; and evaluating communications effectiveness.

Follow the source link below to TMB Issue 22 to read this briefing in full (p.2-7)

-

United Kingdom,

Global

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b22-wb-5th-october-2020.pdf

Consider how to encourage understanding of local COVID-19 restrictions

Research by University College London (UCL) suggests that confidence in understanding coronavirus lockdown restrictions varies greatly across the UK and has dropped significantly since early national measures were put in place in March. As part of their ongoing research UCL determine that people generally consider themselves compliant with restrictions, but UCL caution that this should be interpreted in light of previous reports that show understanding of guidelines are low; therefore possibly reflecting belief in compliance opposed to actual compliance levels. Consider how to ensure residents in lock areas understand the rules that apply to them:

- Make direct contact with resident via social or traditional media, messaging apps, or leafleting through doors to ensure people understand their local restrictions. This may be especially important in combined authority areas as restrictions differ across metropolitan boroughs, the boundaries of which may not be clear to residents

- Encourage the display of digital tools showing local information about which restrictions apply in certain areas. This may be a simple video, or an interactive tool which people could access through localised digital marketing on their smartphones

- Consider where local, clear information could be publicly displayed e.g. digital advertising boards at local bus stops, or localised social media and television adverts

- Consider the demographics, resources and capacities of each community to establish the most appropriate methods of dissemination and key actors who could support this. In Mexico, this included: Video and audio messages shared via WhatsApp; audio messages transmitted via loudspeakers; and banners in strategic locations

-

United Kingdom

https://b6bdcb03-332c-4ff9-8b9d-28f9c957493a.filesusr.com/ugd/3d9db5_3e6767dd9f8a4987940e7e99678c3b83.pdf

Consider how to promote the creation of jobs that support low-carbon economy initiatives

COVID-19 is having an adverse impact on the economy amid the ongoing global climate crisis. Balancing long-term economic recovery and renewal with environmental agendas may be one way to ensure economic growth while mitigating issues such as climate change. One means of achieving this is through renewed commitment from local and national government to invest in, and develop job creation for a low carbon economy. Consider how to encourage low carbon projects including upskilling and training local people in:

- Clean electricity generation and provision of low-carbon heat for homes and businesses e.g. the manufacturing wind turbines, deploying solar PV, installing heat pumps and maintaining energy-system infrastructure

- Installing energy efficiency products ranging from insulation, lighting and control systems

- Providing low-carbon services such e.g. financial, legal and IT, and producing alternative fuels such as bioenergy and hydrogen

- Encouraging low-emission vehicles and the associated infrastructure e.g. electric vehicles, manufacturing batteries, installing electric vehicle charge-points

-

United Kingdom

https://www.ecuity.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Local-green-jobs-accelerating-a-sustainable-economic-recovery_final.pdf

Consider how to utilise partnerships with events security organisations to support COVID-19 marshalling requirements

Many cities have imposed COVID-19 restrictions on the use of public spaces such as social distancing, mask wearing, and number of people allowed to be in a single group to limit the transmission of the virus. Successful implementation of such measures may require additional support from COVID marshals who can provide reassurance to the public and organisations, and help improve compliance with regulations. Organisations that have experience of crowd and people management may have the skills to support the implementation of COVID related restrictions. Consider how trusted events security organisations may be trained to provide COVID marshalling support where needed. This may include:

- Working with supermarkets to protect staff and minimise panic buying; including queue management

- Working in civil contingency roles with local authorities to support town centre patrols in the daytime and night-time economy

- Working with local authorities and law enforcement to help report low level antisocial behaviour and social distance breaches

- Crowd and people management at COVID-19 testing centres

-

United Kingdom

https://showsec.co.uk/news/showsec-show-support-for-civil-contingencies-in-leicester/

Consider learning lessons from COVID-19 response and recovery actions

COVID-19 has created a set of scenarios for which no organisation was fully prepared. Learning lessons from the ways in which people and organisations responded to this crisis is vital for improving future responses and for gathering detailed and timely information to inform recovery and renewal activities. Gathering such information can be achieved through conducting activities to learn lessons.

Approaches to learning lessons

Taking a systems approach to learning lessons can ensure all parts of an organisation, operation, or even individual can be considered. One method particularly relevant to crisis management (and previously applied to this context by government) is the Viable Systems Model (VSM)[1]. To learn lessons across the whole system, VSM advises that 5 systems should be considered:

- Delivery of operations

- Coordination and communication of operations

- Management of processes, systems and planning, including audit

- Intelligence

- Strategy, vision and leadership

These 5 systems are: broad-based; interconnected; provide a balanced framework of strategic, tactical and operational matters; aim for balance across these systems; and ensure nothing is missed or unduly prioritised at the expense of others[2]. As a result, the systems can support the process of learning lessons by structuring the questions to ask. The questions may go beyond the approach of “what went well/not well, and what do differently next time” and, instead, focus on the capabilities of the system.

Drawing on VSM’s 5 systems, we suggest a single question for ‘improvement’ which can be applied to each system to explore the experience and performance of the response, recovery or renewal[3]:

- How could we improve our ‘delivery of operations’?

- How could we improve our ‘coordination and communication of operations’?

- How could we improve our ‘management of processes, systems and planning, including audit’?

- How could we improve our provision and use of ‘intelligence’?

- How could we improve our ‘strategy, vision and leadership’?

Learning lessons can gather information that can be applied while the event is still unfolding[4]. There are number of reasons why gathering lessons need to be done as soon as possible, even as an organisation continues to adapt to COVID-19 conditions. For learning lessons on response to COVID-19 consider[5]:

- The pandemic is still ongoing and waiting until it is over may result in lost institutional memory and learning. While there may be logs of actions and outcomes, the context of these become less meaningful as time goes on and people return to their non-COVI roles

- COVID-19 impacts were swift so there was limited time for organisations to make decisions. Evaluating the actions taken in response will help prepare the next phases and reduce uncertainty whether this is recovery, or a return to a response mode during any second wave

- Understanding how prepared your organisation was for the pandemic is critical, including preparations made once the virus was declared. This will help with future response for health crises and can provide insights into the preparedness and flexibility of the organisation for other types of emergencies

Common issues to be aware of when learning lessons include[6]:

- Scattered or incomplete documentation and contemporaneous evidence. This may have been compiled during the crisis, but not centrally managed meaning it is scattered throughout the organization

- Failure to include external stakeholders in post-event analysis e.g. beneficiaries, partners, customers, investors

- Failure to delegate follow-up actions, including timescales to specific teams or departments with clear deliverables and accountability for actions

Gathering lessons

Lessons can be gathered and learnt in a number of ways, for example, internally within organisations, with external support from other organisations, and from international contexts:

Learning lessons internally

Mechanisms to assess performance and understand lessons learnt internally include impact assessments and debriefs.

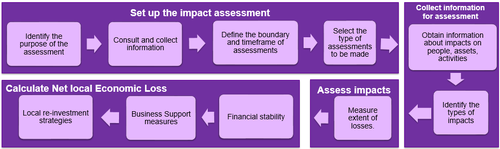

- Impact assessments to learn about the strategic effects of COVID-19 but also learn about specific or emerging system-wide needs, inequalities, and opportunities to improve. This is particularly useful in reflectively considering the outcomes of specific actions and how negative consequences can be prevented or minimised. Guidance on conducting impact assessments can be found in The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B15)[7] which relates to UK National Recovery Guidance[8] that describes the process of conducting an Impact Assessment.

- Debriefing to learn lessons is the process by which a project or mission is reported on in a reflective way, typically, after an event. It is a structured process that reviews the actions taken, and lessons learnt from implementing a project, and its subsequent outcomes. However, instead of only being a post-event activity, learning lessons is important for all stages of managing COVID-19 including preparing, responding and recovering. This will track reflections and learning to ensure information and lessons are not lost and to effectively act on this information to improve future activities.

Learning lessons with external support

Mechanisms to learn lessons from external sources can include:

- Peer reviews which may be most useful to provide an opportunity for a host country, region, city or community to engage in a constructive process to reflect on their activities with a team of independent, expert professionals. Peer reviews can encourage conversation, promote the exchange of best practice, and examine the performance of the entity being reviewed to enhance mutual learning. A peer review can be a catalyst for change and provide benefits for both the host and the reviewers by discussing the current situation, generating ideas, and exploring new opportunities to further strengthen activities in their own context. Guidance on conducting peer reviews is available from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO): ISO 22392: Guidelines for conducting peer reviews[9].

- Learning international lessons is also possible from other analogous contexts. The Manchester Briefing collects such lessons and reviewing what other organisations and countries are doing can help to share insights on practices that are worthy of consideration.

Lessons from internal and external sources can help to reflect on practice and continually improve. But identifying lessons bring a responsibility to prepare to do something better next time using those lessons. This is a particular challenge during intense periods when finding the time to stand back to think about learning is just as pressurised as finding the time to plan to do things differently.

References:

[1] Applying systems thinking at times of crisis https://systemsthinking.blog.gov.uk/author/dr-gary-preece/

[2] The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B16): Week beginning 20th July 2020

[3] The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B17): Week beginning 27th July 2020

[5] https://www.b-c-training.com/bulletin/covid-19-why-you-should-be-conducting-a-debrief-now

[7]The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B15) www.ambs.ac.uk/covidrecovery

Consider conducting local and national surveys to study how COVID-19 is changing daily life

In the UK, first-person accounts of living through the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have been collected to better understand how people respond to pandemics and how to help people cope better in the future. This is particularly important if viral epidemics become more common. This type of research can form an important digital archive for future researchers. Consider working with local and academic organisations to develop an online survey to collate people's experiences on:

- How COVID-19 and the measures to control it are affecting and shaping interactions between individuals in society

- The effect of the pandemic on community wellbeing, quality of life and resilience

- The impact of digital technology on community responses to the spread of coronavirus

- The impact of the pandemic on how and where support can be accessed

How people with physical and mental health problems, and disability, and those who are facing inequality or discrimination have been impacted

-

United Kingdom

https://nquire.org.uk/mission/covid-19-and-you/contribute

-

United Kingdom

https://ourcovidvoices.co.uk/

Consider developing response plans to COVID-19 that incorporate risk to public safety from extremist behaviour

Since the start of the pandemic there has reportedly been an increase in extremist narratives from a variety of groups. People (including vulnerable people who have been severely socially or economically impacted by the pandemic) are at risk of extremism which creates future security challenges. Organisations should remain vigilant about new and emerging threats to public safety and develop response plans that incorporate risks of extremist behaviour. Consider:

- Local assessments of old and new manifestations of local extremism which may have been exacerbated or triggered by the pandemic. Consider the form it takes, (potential) harm caused, and scale of mitigation or response strategies needed

- Developing interventions for those most susceptible to extremist narratives, this may include new groups e.g. a rise in far right groups, and conspiracy theory groups committing arson on 5G towers as they believe them to be the cause of COVID-19

- Assessing groups which have become more at risk since COVID-19 and increased public protections measures and support for these groups e.g. East Asian and South East Asian (since COVID, hate crimes towards this group has increased by 21%)

- Developing COVID-19 cohesion strategy to help bring different communities together to prevent extremist narratives from having significant reach and influence

- Working with researchers and practitioners to build a better understanding of 'what works' in relation to counter extremism online and offline. This should include consideration of dangerous conspiracy theories, and their classification based on the harm they cause

-

United Kingdom

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/906724/CCE_Briefing_Note_001.pdf

Consider how to build public trust and confidence by leading by example

In extraordinary times people turn to their leaders for guidance and reassurance more than ever before. Leading by example helps to unite, connect and guide people in consistently working towards a common goal. Leading by example requires clear, and visible communication of appropriate behaviours. This may include issues such as regular handwashing, adhering to social distancing guidelines, rules on travel, and adhering to isolation and quarantine measures. For example, on facemasks:

- In schools. If headmasters want parents to wear facemasks when they collect children from the playground, then teachers should wear facemasks when they take children into the playground for collection

- In shops. If shops want customers to wear facemasks, then shop workers need to wear facemasks

- In Public. If politicians /police/ local authorities want public to wear facemasks, then they should also do so

-

United Kingdom

https://www.rhrinternational.com/sites/default/files/pdf_files/Leadership-in-Times-of-Uncertainty.pdf

Consider how to manage the return of university students during COVID-19

University students are beginning to return to communal housing located in residential areas. This, alongside rising COVID-19 infections in younger people and fatigue for COVID-19 restrictions, requires consideration of student welfare, and the management of potential transmission. Consider:

- Who should lead the management of a new community of students in cities (e.g. voluntary sector, universities, local authority) including responsibilities for welfare checks, test and trace, GP registration, and food distribution to student households if they are required to isolate

- Providing a point of local support for students, outside of their academic institution, for students who may have moved away from home. Consider partnership with local voluntary sector to coordinate with the local authority such as the OneSlough project which uses 'Community Champions' to provide information and resources to residents

- How the potential movement of students will be managed e.g. if they become ill and decide to go back home, and the impacts of this on potential transmission in two communities i.e. where they reside as students, and their home

- Targeting local online social media influencers to reach younger audiences to communicate COVID-19 messaging and promote track and trace

-

United Kingdom

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/26/more-young-people-infected-with-covid-19-as-cases-surge-globally

-

United Kingdom

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/13/global-report-covid-19-spikes-across-europe-linked-to-young-people

-

United Kingdom

https://www.publichealthslough.co.uk/campaigns/one-slough/

-

United Kingdom

https://theconversation.com/why-the-uk-government-is-paying-social-media-influencers-to-post-about-coronavirus-145478

Consider how to plan and manage repatriations during COVID-19

Crisis planning

The outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in countries closing their borders at short notice, and the suspension or severe curtailing of transport. These measures have implications for those who are not in their country of residence including those working, temporarily living, or holidaying abroad. At the time of the first outbreak, over 200,000 EU citizens were estimated to be stranded outside of the EU, and faced difficulties returning home[1].

As travel restrictions for work and holidays ease amidst the ongoing pandemic, but as the possibility of overnight changes to such easements, there is an increased need to consider how repatriations may be managed. This includes COVID-safe travel arrangements for returning citizens, the safety of staff, and the effective test and trace of those returning home. Facilitating the swift and safe repatriation of people via evacuation flights or ground transport requires multiple state and non-state actors. Significant attention has been given to the amazing efforts of commercial and chartered flights in repatriating citizens, but less focus has been paid to the important role that emergency services can play in supporting repatriation efforts.

In the US, air ambulance teams were deployed to support 39 flights, repatriating over 2,000 individuals. Air ambulance teams were able to supplement flights and reduced over reliance on commercial flights for repatriations (a critique of the UK response[2]). This required monumental effort from emergency service providers. After medical screening or treatment at specific facilities, emergency services (such as police) helped to escort people to their homes to ensure they had accurate public health information and that they understood they should self-isolate.

Authorities should consider how to work with emergency services to develop plans for COVID-19 travel scenarios, to better understand how to capitalise on and protect the capacity and resources of emergency services. Consider how to:

- Develop emergency plans that include a host of emergency service personnel who have technical expertise, and know their communities. Plans should[3]:

- Be trained and practiced

- Regularly incorporate best practices gained from previous lessons learned

- Build capacity in emergency services to support COVID-19 operations through increased staffing and resources

- Anticipate and plan for adequate rest periods for emergency service staff before they go back on call during an emergency period

- Protect emergency service staff. Pay special attention to safe removal and disposal of PPE to avoid contamination, including use of a trained observer[4] / “spotter”[5] who:

- is vigilant in spotting defects in equipment;

- is proactive in identifying upcoming risks;

- follows the provided checklist, but focuses on the big picture;

- is informative, supportive and well-paced in issuing instructions or advice;

- always practices hand hygiene immediately after providing assistance

Consideration can also be given to what happens to repatriated citizens when they arrive in their country of origin. In Victoria (Australia), research determined that 99% of COVID-19 cases since the end of May could be traced to two hotels housing returning travellers in quarantine[6]. Lesson learnt from this case suggest the need to:

- Ensure clear and appropriate advice for any personnel involved in repatriation and subsequent quarantine of citizens

- Ensure training modules for personnel specifically relates to issues of repatriation and subsequent quarantine and is not generalised. Ensure training materials are overseen by experts and are up-to-date

- Strategically use law enforcement (and army personnel) to provide assistance to a locale when mandatory quarantine is required

- Be aware that some citizens being asked to quarantine may have competing priorities such as the need to provide financially.

- Consider how to understand these needs and provide localised assistance to ensure quarantine is not broken

References:

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/649359/EPRS_BRI(2020)649359_EN.pdf

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-53561756

[3] https://ancile.tech/how-to-manage-repatriation-in-a-world-crisis/

[4] https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/ppe-training/trained-observer/observer_01.html

[5] https://www.airmedicaljournal.com/article/S1067-991X(20)30076-6/fulltext

To read this case study in its original format follow the source link below to TMB Issue 21 (p.20-21)

-

Europe,

United Kingdom,

United States of America,

Australia

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b21-wb-21st-september-2020.pdf

Consider increased support for victims of crime as police and court proceedings are delayed due to the pandemic

Vulnerable people

COVID-19 has added thousands more cases to the backlog faced by courts in England and Wales, has delayed proceedings for those already in the justice system, impacted police capacity and could negatively impact reporting of more serious crimes. Delays in processing and handling criminal cases has negative impacts on the health and wellbeing of victims, and could lower confidence in the justice system. Consider how to effectively support those involved in criminal proceedings by:

- Making arrangements with telecoms companies to provide free access to websites that provide information/support to victims of crime to avoid mobile data usage. This should include websites run by organisations such as charities, official government sites (including health), the police, and law courts

- Increasing communications with victims about the progress of their cases. This may require careful partnership working with specialist organisations to mitigate victims' anxieties and create additional capacity for services such as the police, who may be increasingly stretched during COVID

- Ensuring there is support for specialist communications from all partnering organisations. This may include the use of translators, experts able to speak with children, or those with special educational needs

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53238163

-

United Kingdom

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/uk-criminal-justice-system-victim-trial-court-coronavirus-delay-a9422066.html

-

United Kingdom

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/data-charges-removed-for-websites-supporting-victims-of-crime

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52462678

Consider rethinking Renewal

Implementing recovery

We describe perspectives on recovery strategy as it has been broadly configured in relation to a variety of crisis events and the effects that recovery has had. We then elaborate on the idea of Repair as an aspect of Renewal that needs to be considered if we are to attend to the shortcomings of recovery. This briefing takes steps towards putting Repair into practice by offering recommendations for its integration into policy.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 21 (p.2-7).

Consider creating a short, engaging video to explain to the public what Recovery and Renewal means in their local area

Local government are producing online materials to help people understand what has happened during response and what is meant by the next phase of COVID-19. This can communicate expectations and align aspirations for what recovery may involve. Consider:

- Producing a short video on how the response effort aims to support people and businesses

- Producing a short video on Recovery and Renewal

- Encouraging widespread dissemination of the video to households, classrooms, offices, waiting rooms, public spaces, social media

- Reach the widest audience by providing the video in different languages

Watch Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council's video: https://www.barnsley.gov.uk/services/health-and-wellbeing/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-covid-19-recovery-plan-for-barnsley/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.barnsley.gov.uk/services/health-and-wellbeing/covid-19-coronavirus-advice-and-guidance/covid-19-recovery-plan-for-barnsley/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTvDF-Z7Rjo

Consider how to effectively publicise that some people are exempt from wearing face coverings

Some people who are not able to not wear a face covering are reporting being confronted in enclosed public places and, as a result, being fearful and unwilling to leave their homes. Consider:

- Information campaigns to make the public aware that some people may not be able to wear face coverings. For example, the UK government provides three 'reasonable' reasons for not wearing a covering:

- You have a physical/mental illness, impairment, or disability that means you cannot put on, wear or remove a face covering

- Putting on, wearing or removing a face covering would cause you severe distress

- You are travelling with/providing assistance to, someone who relies on lip-reading

- Whether it is appropriate to encourage those who cannot wear a face covering to get an exemption card or wear an exemption badge to reduce the likelihood of confrontation

Example face covering exemption card: https://hiddendisabilitiesstore.com/hidden-disabilities-face-covering.html

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-53827911

Consider measures to reduce youth unemployment due to COVID-19

In the UK, it is expected that youth unemployment will rise by over 640,000 in 2020 taking the total to over 1 million. Under 25s may face years of reduced pay and limited job prospects long-term. Consider strategies to tackle youth unemployment:

- Encourage organizations to develop partnerships with UK employers, government, education institutions, and civil society to create quality work placements for young people

- Promote the benefits of employer networks e.g. lower recruitment costs and improved staff retention to facilitate more work placements

- Consider measures such as the ‘EU measure against youth unemployment’. The Commission wants EU countries to increase their support for the young through their recovery and suggest member states should invest at least €22 billion for youth employment. Initiatives also include:

- Youth Employment Support which includes The Youth Guarantee which aims to ensure people under the age of 25 get a good-quality offer of employment, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education.

- Extending the Youth Guarantee which covers people aged 15 - 29 (previously the upper limit was 25) and:

- Reaches out to vulnerable groups, such as minorities and young people with disabilities

- Provides tailored counselling, guidance and mentoring

- Reflects the needs of companies, providing the skills required and short preparatory courses

-

United Kingdom

https://www.mancunianmatters.co.uk/news/20082020-coronavirus-youth-job-crisis-how-to-beat-it/

Consider Renewal of local government following COVID-19: Reoganisation, Devolution and Institutional Change in English Government

Legislation

Consider the use of mass testing to complement test and trace capabilities

Test and trace systems have been implemented worldwide to try to track and contain the transmission of COVID-19. While these efforts have been broadly successful, there are some communities in which the test and trace process is inefficient due to limited uptake[1]. This has been particularly relevant in communities where there are language barriers[2], and in work environments in which sharing colleague’s information may be difficult because a positive result could mean unpaid sick days[3]. Commonly, such occupations include those with a large number of migrant workers, or where workers are employed through agencies and staff members are inconsistent or turnover is high[4]. In these cases alternative mechanisms such as mass swabbing through mobile testing units have been employed to try to boost the number of people tested, including those who may be asymptomatic[5]. Taking swabs can be unpleasant, however, using saliva samples can be less invasive, more reliable than nasal swabs, and can be done more frequently, even once a week which would help mitigate the false negatives swabs can produce[6].

Targeted mass swabbing is currently being undertaken in some countries such as Canada, where there have been outbreaks and deaths of those working in agriculture due to poor living and working conditions5. The vulnerability of these groups to COVID-19 was addressed in The Manchester Briefing 13 where it addressed localised spikes in COVID-19 transmission as a result of poor working conditions in food and garment industries.

Mass swabbing could help to mitigate the lack of reporting to contact tracers, improve the transparency of information within the health system, and improve the efficiency of testing[7]. Efficient mass testing should consider:

- Effectively mapping all existing testing and laboratories capabilities including those in health services, research centres[8], and scientific institutes to reduce the risk of running parallel systems with the private sectors which may encourage competition for supplies and potentially reduce the capacity of existing systems13

- Use existing capacities to help develop important localised approaches to improve the coordination of mass testing through involvement with local authorities and industries13

- Develop partnerships with life science industries to build resources and capacity for mass testing14 that should account for, and complement, existing local capacity

- Be mindful of how targeted mass testing may (further) stigmatise certain communities. Careful consideration should be given to the location of testing centres so not to create an association between a particular community and the virus

- Ensure there is clear and simple dissemination of public information in areas in which mass testing takes place. This should include sensitivity to the local conditions including languages, culture and the level of community (dis)harmony

Increasing effective capacity for mass testing, especially in high risk populations, is central to limiting the spread of COVID-19. Developing an integrated localised system that is capable of regular, repeat testing may not only help stem the spread of the virus, it may also help support other sectors adversely affected by COVID-19. For example, this type of testing may help mitigate the issue of quarantine after travel as the virus can be more closely monitored, even in asymptomatic patients. In addition, particularly vulnerable groups may be protected through close observation, including those who work in jobs where there is a high risk of infection, and those who may feel forced to go to go to work due to financial insecurity.

[7] https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/a-hidden-threat-test-and-trace-failure-edges-closer

To read this case study in its original format, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 20 (p.22-23).

Consider disability-inclusive recovery and renewal from COVID-19

Inclusive recovery practices are essential as additional groups of vulnerable people emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside data on the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable and marginalised people. In particular, people living with visible and invisible disabilities have been adversely impacted by the virus due to challenges in accessing health services, and because they are at greater risk of experiencing complex health needs, worse health outcomes, and stigma[1].

While disability alone may not be related to an increased risk of contracting COVID-19, some people with disabilities might be at a higher risk of infection or severe illness because of their underlying medical conditions[2]. In particular, “adults with disabilities are three times more likely than adults without disabilities to have heart disease, stroke, diabetes, or cancer than adults without disabilities”2. In the UK, working-age women with a disability are more than 11 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than women without a disability, and for men, the death rate was 6.5 times higher than for men without a disability[3].

Health-care staff should be provided with rapid awareness training on the rights and diverse needs of people living with disabilities to maintain their dignity, safeguard against discrimination, and prevent inequities in care provision[4]. Advice on how to do this is extremely important. In the UK, guidance on how to safely care for people with disabilities is provided to protect carers and the person they are caring for, and includes consideration of[5]:

- Protecting yourself and the person you care for e.g. appropriate use of PPE in specific settings

- Supporting the person you care for through change e.g. providing accessible information

- Maintaining the health and wellbeing of carers

In recovery, some people with disabilities may have restricted access to social networks, systems that provide support, job security, consistency of income, education – aspects that others may take for granted. “The more a person is excluded, the more challenging the recovery, and persons with disabilities often fall in this category.”[6] Recovery from COVID-19 must therefore reflect disability-inclusive strategies to provide action-oriented directions for government officials and decision makers responsible for post-disaster recovery and reconstruction.

The Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Recovery Guidance Note[7] developed by the World Bank / Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) aims to accelerate global action to address the needs of persons with disabilities. Overall, the World Bank and GFDRR estimate that a quicker and more inclusive recovery could reduce losses to well-being by $65 billion a year[8].

Disability-inclusive recovery is about including people with disabilities in recovery planning and enabling equal opportunities through the removal of barriers. This can be done by gathering baseline disability data and incorporating it into needs assessments, by mainstreaming disability inclusion in recovery programmes, and by recommending specific interventions. There are four essential steps to support inclusive risk planning:[9]

- Collect data on barriers and accessibility improvements to understand and assess disability inclusion in recovery and reconstruction

- Adopt appropriate disability legislation to support a disability-inclusive recovery process that will prioritize needs and allocate resources. New policies should be in alignment with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to guide disability-inclusive recovery and reconstruction

- Establish institutional mechanisms to ensure the meaningful participation of persons with disabilities in the planning and designing of recovery and reconstruction processes. Also identify and designate an agency with responsibility for coordinating and overseeing disability affairs in recovery and reconstruction. Additionally, ensure standards for disability inclusion in recovery are established and communicated

- Target households and groups that have limited ability to self-recover, including households with persons with disabilities, to receive financial support and other interventions. Set standards for disability inclusion in budgeting and procurement quickly and ensure they are applied across the recovery and reconstruction process. Also require full consideration of accessibility, including the principles of universal design, as a condition of financial contributions and assistance by all involved in recovery.

Disability-inclusive recovery can help reduce poor representation of people living with disabilities in post-disaster recovery efforts. This provides an opportunity to build a more accessible environment that is inclusive and resilient to future disasters, and to reduce the disproportionate risks faced by people living with disabilities by[10]:

- Making infrastructure resilient and accessible (barrier-free buildings and land use planning)

- Setting up programs to actively employ persons with disabilities, such as hiring them in the recovery and reconstruction planning and implementation process

- Making healthcare and education readily available and ensuring healthcare is accessible to persons with disabilities before and after a disaster

- Communicating hazard exposure and risk information in a way that can be understood and acted upon (for example, sign language interpretation and plain language)

- Improved accessibility before and after a disaster also benefits older people, those who are ill or have been injured, pregnant women, and some indigenous and non-native language speakers

Recovery is often tumultuous and traumatic, but it is also an opportunity to renew systems and processes by understanding and addressing unequal practices and structures. By making disability inclusion a priority in the recovery agenda, we can ensure more self-sufficient, inclusive, and resilient societies for all.

[1] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30076-1/fulltext

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53221435

[4] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30076-1/fulltext

[8] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30076-1/fulltext

[9] https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/ensuring-equitable-recovery-disability-inclusion-post-disaster-planning

[10] https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/ensuring-equitable-recovery-disability-inclusion-post-disaster-planning

To read this case study in its original format follow the source link below to TMB Issue 19 (p.15-16).

-

United Kingdom,

Global

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b19-wb-24th-august-2020.pdf

Consider how to manage change for COVID-19 recovery

Crisis planning

Implementing recovery

We propose key considerations for local governments when managing wide-ranging change, such as that induced by a complex, rapid and uncertain events like COVID-19. Identifying and understanding the types of change and the extent to which change can be proactive rather than reactive, can help to support the development of resilience in local authorities and their communities.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 19 (p.2-6).

Consider providing fact-checking services to counter misinformation on COVID-19

There is a glut of information on COVID-19 and more often we are seeing news outlets attempting to check and correct misinformation that be being shared. This should aim to ensure that the public have conclusions about the virus which are substantiated, correct, and without political interference. Myths can be debunked, misinformation corrected, and poor advice challenged. Consider whether to:

- Provide your own fact-checking website

- Contribute to others' fact-checking sources

- Check facts of colleagues and partners to ensure correct information prevails

- Remind others of the importance of not spreading misinformation and checking other peoples' facts

- Link your website to official sources of information so not to promulgate misinformation

-

United States of America

https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2020/03/17/could-that-be-true-sorting-fact-fiction-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.cdhn.org/covid-19-fact-checks

-

United Kingdom

https://fullfact.org/health/coronavirus/

Consider the wider health and wellbeing implications of COVID-19 including those associated with lockdown

The health impacts of COVID-19 such as organ scarring, and long-term lung problems are gradually coming to light. However, wider implications from lockdown on working socialising and living in small spaces is less understood. Consider the impacts of this and the steps that can be taken to address them:

- Eye strain. Consider the amount of time being spent on online calls e.g. on Zoom or Skype:

- Where possible replace Zoom with phone calls

- Make meetings shorter and limit them to 40 minutes

- Use the 20/20/20 rule. In a 40 minute meeting, take a mid-time break to rest your eyes and look at something 20 feet away for 20 second

- Back pain. Consider impacts of home working environments on back pain such as working from the sofa:

- Ensure employees have a set-up that's fit for purpose like they do at their office

- Do not stay seated all day as the spine is out of alignment - set reminders to walk every hour for a few minutes or do simple stretches

- Circulation. Improve awareness of the risk from poor circulation as a result of moving less:

- Look for signs of varicose veins such as aching legs, swollen ankles, and red or brown stains around the ankles

- Keep hydrated and mobile to decrease the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or clotting in the deep veins of the legs

- Maintain contact with your doctor as DVT is associated with underlying health issues that may go undiagnosed

Consider advising consumers about purchasing safely online

During lockdown more consumers have been turning to online shopping. Action Fraud, the UK’s national reporting centre for fraud and cybercrime, received over 16,000 reports about online fraud during the lockdown totalling over £16m. Consumers report buying mobile phones (19%), vehicles (22%), and electronics (10%) on sites such as eBay (18%), Facebook (18%), and Gumtree (10%) only for the items to never arrive. Considering reinforcing to citizens:

- The prevalence of online fraud

- Actions to make online shopping safer e.g.

- choose a trusted retailers or build confidence in the retailer by researching other consumers’ experiences

- create accounts that have strong passwords that are not identical to email accounts

- be aware of scam email messages offering deals and don’t click on links that you are unsure about

- use a credit card to pay as it offers more payment protection

- What they should do if they think they have become a victim of online shopping fraud e.g.

- note the website’s address, close the browser, report to a consumer fraud advice service

- monitor bank transactions if payment details have been submitted to the site

- contact your bank about any unrecognised transactions, however small

-

United Kingdom

https://www.actionfraud.police.uk/

Consider developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response (Part 3): Assessing performance

Crisis planning

Implementing recovery

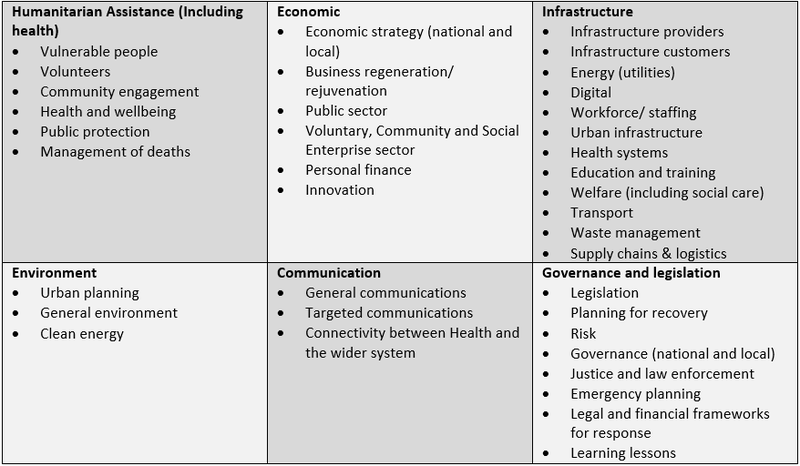

Part 3: Building on TMB 16 and 17, we present a detailed view of how to assess the performance of the system of resilience before/during/after COVID-19. This briefing presents a comprehensive Annex of aspects against which performance can be considered.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 18 (p.2-7).

Consider establishing a relief fund for the public and businesses to contribute financially to recovery

During response, individuals and organisations have shown a huge outpouring of support through donations of their time and resources. Now, with people going back to work and assuming their pre-COVID activities, people and organisations may have less time to volunteer to the effort, or there may be less suitable volunteer opportunities available. Instead, people may want to show their solidarity in other ways, including by making financial donations. Consider establishing a relief fund, and publicizing its cause, to give an organised mechanism for people and businesses to show their solidarity. An organised mechanism should give people confidence that their donations will be governed appropriately.

-

Barbados,

Canada

https://reliefweb.int/report/barbados/government-canada-and-cdb-establish-new-fund-support-disaster-risk-management

-

United Kingdom

https://nationalemergenciestrust.org.uk/

Consider how different emergency services have supported COVID-19 response efforts

The all-of society impact of COVID-19 has required many organisations to adapt their operating procedures and deliver alternative activities, including frontline emergency services such as the Police, Fire Brigade, Ambulance and Search and Rescue organisations. We provide examples of first responder adaptation during COVID-19 to demonstrate how frontline services have modified their operations to help tackle the crisis.

Alternative activities undertaken by emergency services

- Supporting health and social care: In California (USA), the National Guard deployed rapid medical strike teams to assist overwhelmed health/nursing facilities[1]. Strike teams involved 8-10 people (e.g. included doctors, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, behavioural health professionals). Strike teams worked across 25 nursing homes – staying on-site for 3-6 days to establish stability of care, disinfected facilities, and staffed mobile COVID-19 testing sites2.

- House-to-house testing: In Guayaquil (Ecuador)municipal taskforces (involving firefighters, medics, and city workers) went house-to-house looking for potential cases[2] . Similarly, in Cambridge (USA), Fire Department paramedics were enlisted to go door-to-door in public housing developments that predominantly housed the elderly and younger disabled tenants to offer Covid-19 tests to residents[3]

- Disinfecting public spaces: In Pune (India) , sanitary workers disinfected and fumigated public areas[4]

- Managing sanitation services: In Ganjam (India), the fire brigade supported the COVID-19 effort by heading the country’s sanitation programme[5]

- Delivering food/medication parcels to vulnerable people: In West Bengal (India), all police stations were made responsible for delivering food and medication to those who are vulnerable and sheltering to avoid food scarcity - the programme was monitored by the State’s District Magistrates and Police Superintendents[6]. In Georgia (USA), a similar scheme involved police officers delivering groceries/medicine to vulnerable people who had placed/paid for orders[7]

- Distributing $100 gift cards: In Smyrna (USA), police handed out $100 gift cards from a community grocery assistance fund to help vulnerable residents purchase essential items[8]

- Counteracting misinformation: In Göttingen (Germany), clashes with tower block residents under enforced lockdown were caused by communication problems between authorities and residents. Translators, working through first responding services, communicated important public health information to relevant residents in German and Romanian via text messaging[9]

Consider the demand for alternative activities from emergency services

To determine how, when and where emergency services can support alternative activities, consider:

- The demand for alternative support:

- Identify current needs where additional capacity to deliver activities is required

- Identify future areas where demand is foreseeable, and where additional capacity may need to be built e.g. through retraining

- How responders can support alternative activities[10]:

- Identify potential capacity in responder organisations, or how this capacity can be created, protected, and prioritised, and how long this capacity may be available[11]

- Obtain strategic-level agreement on the direction, scope and parameters of the alternative activities

- Gather information to understand activities e.g. from partner databases, existing measures, knowledgeable people

- Assess the impact of redeploying staff to other activities and the effects of this on their ability, and the organisation’s ability to cope[12]

- Preparing redeployed resources:

- Identify and source training and safety measures required to redeploy staff to alternative activities (including health and wellbeing of staff and the public)[13]

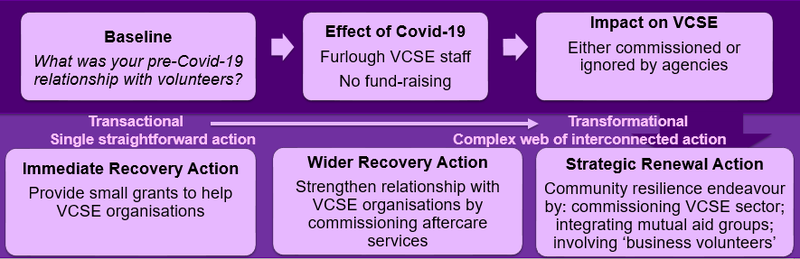

- Capability of the resources, including:

- Transactional activities i.e. single short-term actions

- Transformational activities i.e. complex, interconnected, longer-term actions needing strategic partnerships

Consider the benefits to the emergency services from delivering alternative activities

The involvement of emergency services in alternative activities has the potential to increase services’ visibility in communities which can help build community trust and engagement[14], reduce misinformation and non-compliance to COVID-19, and bolster local multi-agency partnerships for a more efficient and effective response and recovery[15].

On benefits, consider:

- Working with partners to capitalise on increased contact with marginalised and vulnerable communities e.g. from door-to-door visits. This may include:

- Addressing additional social or health issues, fire safety, safeguarding, or referral to other services

- Community engagement activities and visible street presence through renewing the Neighbourhood Watch Scheme and police Safer Neighbourhood Teams[16]

- Developing joint local/national approaches to provide alternative response to support COVID-19 activities. This may include:

- Emergency services delivering essential items like food and medicines to vulnerable people, driving ambulances, assisting ambulance staff, attending homes of people who have fallen but are not injured[17],[18]

- Increase multi-agency coordination with civil organisations should be central in the design and review measures for COVID-19 response and recovery[19]

- How to capitalise on increased community engagement and volunteerism to help disseminate public health information. Consider working with volunteer and civil society organisations that are close to communities and know their specific needs to:

- Increase capacity for response and recovery considering short and long-term requirements of the need, and of volunteers

- Translate and disseminate timely information in relevant languages and tackle misinformation[20]

- Build relationships in the community to encourage adherence to COVD-19 behaviours, especially with people who have not had previous contact with emergency services

- Enhance community engagement and information sharing to combat misinformation and non-compliance about COVID-19 working with Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships (CDRPs)18

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/ecuador-guayaquil-mayor-

[4] http://cdri.world/casestudy/response_to_covid19_by_pune.pdf

[7] https://cobbcountycourier.com/2020/04/smyrna-police-deliver-food-and-medicine-to-seniors/

[8] https://cobbcountycourier.com/2020/04/smyrna-police-deliver-food-and-medicine-to-seniors/

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-53131941

[11] https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NGA-Memo_Concurrent-Emergencies_FINAL.pdf

[12] https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/strategy/resourcing/transferable-skills-redeploying-during-COVID-19

[15] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25788&LangID=E

[16] https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Policing-a-Pandemic.pdf

[19] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25788&LangID=E

Consider how the voluntary sector can receive support to write proposals for COVID-19 funding

In many countries the voluntary sector is struggling financially as a result of loss of income and increased demand for services. The sector is a critical part of society and provides important services, so funding is being made available. Competition for that funding is high and the process to secure funding is not always straightforward; with application forms and procedures to follow. To support the voluntary sector to secure funding, consider supporting the writing of funding applications. Consider how to:

- Find out from voluntary organisations what they need to be able to make successful bids for funding

- Produce regular newsletters that summarise funding opportunities so voluntary organisations know what funding is available

- Provide help to voluntary organisations to interpret the calls for funding and identify suitability

- Provide information on how to write a successful application (e.g. online resources, training courses)

- Find volunteers who have grant writing skills and embed them in voluntary organisations (e.g. volunteers from the organisation itself, university students, furloughed staff from other organisations)

- Provide samples of good proposals to show the benchmark, support project managers on how to successfully deliver funded projects (e.g. project governance, staffing, delivery, evaluation)

Consider how your policy changes put people and their rights at the centre

Implementing recovery

National Voices, a coalition of English health and social care charities, published its report on 'Five principles for the next phase of the COVID-19 response'. Their five principles seek to ensure that policy changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic meet the needs of people and engage with citizens affected most by the virus and lockdown, especially those with underlying health concerns. They advocate that the future should be more compassionate and equal, with people's rights at its centre. The principles have been developed based on dialogues with hundreds of charities and people living with underlying health conditions. Consider how your policy changes:

- Actively engage with, consult, co-produce, and act on the concerns of those most impacted by policy changes that may profoundly affect their lives

- Make everyone matter, leave no-one behind as all lives, all people, in all circumstances, matter so needs to be weighed up the same in any Government policy

- Confront inequality head-on as, "we're all in the same storm, but we're not all in the same boat" e.g. difference in finances, work/living conditions, personal characteristics

- Recognise people, not categories, by strengthening personalised care and rethinking the category of 'vulnerable' to be more holistic, beyond health-related vulnerabilities

- Value health, care, connection, friendship, and support equally as people need more than medicine, and charities and communities need to be enabled to help

-

United Kingdom

https://www.nationalvoices.org.uk/sites/default/files/public/publications/5_principles_statement_250620.pdf

Consider the compounding effects of COVID-19 on LGBTQ+ people

COVID-19 has exacerbated the health and social care inequalities experienced by LGBTQ+ people as they are likely to living with conditions that impact their health and well-being. LGBTQ+ people are at high risk of pre-existing poor mental health; social isolation; substance misuse; living in unsafe environments; financial instability; homelessness; and negative experiences with health services as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Consider partnering with LGBTQ+ organisations to:

- Support test track and trace. The LGBT Foundation's community survey on COVID-19found that: 64% of respondents would rather receive COVID-19 support from an LGBT specific organisation. This rises in other LGBTQ+ groups to: 71% of Black, Asian and minority ethnic LGBT people; 69% of disabled LGBT people, 76% of trans people and 74% of non-binary people

- Collect sexual orientation and trans status data alongside COVID-19 transmission and infection data to provide reliable data on the impact of COVID-19 on LGBTQ+ people

- Provide safe accommodation during COVID-19; 8% of respondents to the LGBT Foundation's community survey said they felt unsafe where they were currently staying

- Prepare for the hospitalisation of trans people (e.g. allocation to wards with the gender they identify with, or providing private areas)

-

United Kingdom

https://www.nationalvoices.org.uk/blogs/how-cv19-pandemic-affecting-people-lgbtq-communities

-

United Kingdom

https://lgbt.foundation/coronavirus/hiddenfigures

Consider the impacts of COVID-19 on sex workers

COVID-19 has been a struggle for client-facing businesses - and sex work is no different[1]. What complicates support for those in sex work is the stigmatisation and lack of recognition workers receive[2]. Sex workers are less likely to seek, or even be eligible for, government-led social protection or economic initiatives to support small businesses[3] which has proved a serious issue during COVID-19. Most sex work has ceased due to social distancing and travel restrictions, leaving many marginalised, and economically precarious people even more vulnerable[4]. While some sex workers have been trying to move their work online4, many have been financially compromised3 resulting in potentially unsafe practices, both in terms of contracting COVID-19, and increased risk of homelessness and abuse[5]

Sex worker-led organisations have therefore had to set up hardship funds to fill the gap left by exclusionary government policies2. Such policies are demonstrated by delays in opening licensed sex work premises in Germany, where sex work is legal[6]. The Association of Sex Workers in Germany argued that brothels “could easily incorporate pandemic safety measures adopted by other industries, including face masks, ventilating premises and recording visitors’ contact details”6. Such measures have been successful in Zambia where authorities were able to trace a number of COVID-19 cases working with sex workers as investigations aimed not to “stigmatise or discriminate against them”[7].

Key interventions to address the impacts of COVID-19 among sex workers have been identified, with a view that “all interventions and services must be designed and implemented in collaboration with sex-worker-led organisations”[3]. These include[3]:

- Providing financial benefits and social protection for all sex workers, including migrants with illegal or uncertain residency status

- Stopping arrests and prosecutions for sex work which have been shown to be harmful to health

- Targeting health promotion advice on prevention of COVID-19 with language translation

- Distributing of hand sanitiser, soap, condoms, and personal protective equipment

- Maintaining and extending person-centred services to address needs e.g. mental health, substance use, physical and sexual violence, and sexual and reproductive health

- COVID-19 testing and contact tracing among sex workers

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-52183773

[3] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31033-3/fulltext

[4] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52821861

[5] https://www.swarmcollective.org/blog

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-52604961

To read this case study in its original format, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 17 (p.18).

Developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response (Part 2) - Debriefing using the Viable Systems Model (VSM)

Crisis planning

Consider developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response

Crisis planning

Part 1: We begin by exploring how the experience of COVID-19 prompts consideration of what national and local (ambitious) renewal of systems to develop resilience to crises and major emergencies could look like. We present a model of 5 systems: operational delivery; coordination; management; intelligence; and policy. This briefing elevates thinking from the performance of individual organisations into considering the performance of the system as a whole.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 16 (p.2-7).

Consider supporting children with autism and their parents during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenging time for everyone, especially in trying to adjust to new routines and living and working environments. This may be particularly true for children with autism and their parents, as children with autism have trouble adjusting to, coping with, and understanding change. To help with this, help parents to explain the current situation in clear and simple ways and can help children with autism to adjust to the 'new normal'. One way of doing this is to provide parents with access to materials that frame COVID-19 as a germ that can make people sick, so it is important to stay away from others and not touch things.

Advise parents to reiterate important rules to children with autism is also important to help them cope, such as: