Lessons for Resilience

Consider co-designing response and communication strategies with the public

Guest briefing by Dr. Su Anson and Dr. Katrina Petersen, Trilateral Research and Inspector Sue Swift, Lancashire Constabulary, prompts thinking on risk communication approaches in the context of COVID-19 and how the public can be active agents in their own response. The authors focus on: Identifying goals and outcomes; developing the message; channels for two-way engagement; and evaluating communications effectiveness.

Follow the source link below to TMB Issue 22 to read this briefing in full (p.2-7)

-

United Kingdom,

Global

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b22-wb-5th-october-2020.pdf

Consider how to encourage understanding of local COVID-19 restrictions

Research by University College London (UCL) suggests that confidence in understanding coronavirus lockdown restrictions varies greatly across the UK and has dropped significantly since early national measures were put in place in March. As part of their ongoing research UCL determine that people generally consider themselves compliant with restrictions, but UCL caution that this should be interpreted in light of previous reports that show understanding of guidelines are low; therefore possibly reflecting belief in compliance opposed to actual compliance levels. Consider how to ensure residents in lock areas understand the rules that apply to them:

- Make direct contact with resident via social or traditional media, messaging apps, or leafleting through doors to ensure people understand their local restrictions. This may be especially important in combined authority areas as restrictions differ across metropolitan boroughs, the boundaries of which may not be clear to residents

- Encourage the display of digital tools showing local information about which restrictions apply in certain areas. This may be a simple video, or an interactive tool which people could access through localised digital marketing on their smartphones

- Consider where local, clear information could be publicly displayed e.g. digital advertising boards at local bus stops, or localised social media and television adverts

- Consider the demographics, resources and capacities of each community to establish the most appropriate methods of dissemination and key actors who could support this. In Mexico, this included: Video and audio messages shared via WhatsApp; audio messages transmitted via loudspeakers; and banners in strategic locations

-

United Kingdom

https://b6bdcb03-332c-4ff9-8b9d-28f9c957493a.filesusr.com/ugd/3d9db5_3e6767dd9f8a4987940e7e99678c3b83.pdf

Consider learning lessons from COVID-19 response and recovery actions

COVID-19 has created a set of scenarios for which no organisation was fully prepared. Learning lessons from the ways in which people and organisations responded to this crisis is vital for improving future responses and for gathering detailed and timely information to inform recovery and renewal activities. Gathering such information can be achieved through conducting activities to learn lessons.

Approaches to learning lessons

Taking a systems approach to learning lessons can ensure all parts of an organisation, operation, or even individual can be considered. One method particularly relevant to crisis management (and previously applied to this context by government) is the Viable Systems Model (VSM)[1]. To learn lessons across the whole system, VSM advises that 5 systems should be considered:

- Delivery of operations

- Coordination and communication of operations

- Management of processes, systems and planning, including audit

- Intelligence

- Strategy, vision and leadership

These 5 systems are: broad-based; interconnected; provide a balanced framework of strategic, tactical and operational matters; aim for balance across these systems; and ensure nothing is missed or unduly prioritised at the expense of others[2]. As a result, the systems can support the process of learning lessons by structuring the questions to ask. The questions may go beyond the approach of “what went well/not well, and what do differently next time” and, instead, focus on the capabilities of the system.

Drawing on VSM’s 5 systems, we suggest a single question for ‘improvement’ which can be applied to each system to explore the experience and performance of the response, recovery or renewal[3]:

- How could we improve our ‘delivery of operations’?

- How could we improve our ‘coordination and communication of operations’?

- How could we improve our ‘management of processes, systems and planning, including audit’?

- How could we improve our provision and use of ‘intelligence’?

- How could we improve our ‘strategy, vision and leadership’?

Learning lessons can gather information that can be applied while the event is still unfolding[4]. There are number of reasons why gathering lessons need to be done as soon as possible, even as an organisation continues to adapt to COVID-19 conditions. For learning lessons on response to COVID-19 consider[5]:

- The pandemic is still ongoing and waiting until it is over may result in lost institutional memory and learning. While there may be logs of actions and outcomes, the context of these become less meaningful as time goes on and people return to their non-COVI roles

- COVID-19 impacts were swift so there was limited time for organisations to make decisions. Evaluating the actions taken in response will help prepare the next phases and reduce uncertainty whether this is recovery, or a return to a response mode during any second wave

- Understanding how prepared your organisation was for the pandemic is critical, including preparations made once the virus was declared. This will help with future response for health crises and can provide insights into the preparedness and flexibility of the organisation for other types of emergencies

Common issues to be aware of when learning lessons include[6]:

- Scattered or incomplete documentation and contemporaneous evidence. This may have been compiled during the crisis, but not centrally managed meaning it is scattered throughout the organization

- Failure to include external stakeholders in post-event analysis e.g. beneficiaries, partners, customers, investors

- Failure to delegate follow-up actions, including timescales to specific teams or departments with clear deliverables and accountability for actions

Gathering lessons

Lessons can be gathered and learnt in a number of ways, for example, internally within organisations, with external support from other organisations, and from international contexts:

Learning lessons internally

Mechanisms to assess performance and understand lessons learnt internally include impact assessments and debriefs.

- Impact assessments to learn about the strategic effects of COVID-19 but also learn about specific or emerging system-wide needs, inequalities, and opportunities to improve. This is particularly useful in reflectively considering the outcomes of specific actions and how negative consequences can be prevented or minimised. Guidance on conducting impact assessments can be found in The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B15)[7] which relates to UK National Recovery Guidance[8] that describes the process of conducting an Impact Assessment.

- Debriefing to learn lessons is the process by which a project or mission is reported on in a reflective way, typically, after an event. It is a structured process that reviews the actions taken, and lessons learnt from implementing a project, and its subsequent outcomes. However, instead of only being a post-event activity, learning lessons is important for all stages of managing COVID-19 including preparing, responding and recovering. This will track reflections and learning to ensure information and lessons are not lost and to effectively act on this information to improve future activities.

Learning lessons with external support

Mechanisms to learn lessons from external sources can include:

- Peer reviews which may be most useful to provide an opportunity for a host country, region, city or community to engage in a constructive process to reflect on their activities with a team of independent, expert professionals. Peer reviews can encourage conversation, promote the exchange of best practice, and examine the performance of the entity being reviewed to enhance mutual learning. A peer review can be a catalyst for change and provide benefits for both the host and the reviewers by discussing the current situation, generating ideas, and exploring new opportunities to further strengthen activities in their own context. Guidance on conducting peer reviews is available from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO): ISO 22392: Guidelines for conducting peer reviews[9].

- Learning international lessons is also possible from other analogous contexts. The Manchester Briefing collects such lessons and reviewing what other organisations and countries are doing can help to share insights on practices that are worthy of consideration.

Lessons from internal and external sources can help to reflect on practice and continually improve. But identifying lessons bring a responsibility to prepare to do something better next time using those lessons. This is a particular challenge during intense periods when finding the time to stand back to think about learning is just as pressurised as finding the time to plan to do things differently.

References:

[1] Applying systems thinking at times of crisis https://systemsthinking.blog.gov.uk/author/dr-gary-preece/

[2] The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B16): Week beginning 20th July 2020

[3] The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B17): Week beginning 27th July 2020

[5] https://www.b-c-training.com/bulletin/covid-19-why-you-should-be-conducting-a-debrief-now

[7]The Manchester Briefing on COVID-19 (B15) www.ambs.ac.uk/covidrecovery

Consider conducting local and national surveys to study how COVID-19 is changing daily life

In the UK, first-person accounts of living through the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have been collected to better understand how people respond to pandemics and how to help people cope better in the future. This is particularly important if viral epidemics become more common. This type of research can form an important digital archive for future researchers. Consider working with local and academic organisations to develop an online survey to collate people's experiences on:

- How COVID-19 and the measures to control it are affecting and shaping interactions between individuals in society

- The effect of the pandemic on community wellbeing, quality of life and resilience

- The impact of digital technology on community responses to the spread of coronavirus

- The impact of the pandemic on how and where support can be accessed

How people with physical and mental health problems, and disability, and those who are facing inequality or discrimination have been impacted

-

United Kingdom

https://nquire.org.uk/mission/covid-19-and-you/contribute

-

United Kingdom

https://ourcovidvoices.co.uk/

Consider developing response plans to COVID-19 that incorporate risk to public safety from extremist behaviour

Since the start of the pandemic there has reportedly been an increase in extremist narratives from a variety of groups. People (including vulnerable people who have been severely socially or economically impacted by the pandemic) are at risk of extremism which creates future security challenges. Organisations should remain vigilant about new and emerging threats to public safety and develop response plans that incorporate risks of extremist behaviour. Consider:

- Local assessments of old and new manifestations of local extremism which may have been exacerbated or triggered by the pandemic. Consider the form it takes, (potential) harm caused, and scale of mitigation or response strategies needed

- Developing interventions for those most susceptible to extremist narratives, this may include new groups e.g. a rise in far right groups, and conspiracy theory groups committing arson on 5G towers as they believe them to be the cause of COVID-19

- Assessing groups which have become more at risk since COVID-19 and increased public protections measures and support for these groups e.g. East Asian and South East Asian (since COVID, hate crimes towards this group has increased by 21%)

- Developing COVID-19 cohesion strategy to help bring different communities together to prevent extremist narratives from having significant reach and influence

- Working with researchers and practitioners to build a better understanding of 'what works' in relation to counter extremism online and offline. This should include consideration of dangerous conspiracy theories, and their classification based on the harm they cause

-

United Kingdom

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/906724/CCE_Briefing_Note_001.pdf

Consider how to plan and manage repatriations during COVID-19

Crisis planning

The outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in countries closing their borders at short notice, and the suspension or severe curtailing of transport. These measures have implications for those who are not in their country of residence including those working, temporarily living, or holidaying abroad. At the time of the first outbreak, over 200,000 EU citizens were estimated to be stranded outside of the EU, and faced difficulties returning home[1].

As travel restrictions for work and holidays ease amidst the ongoing pandemic, but as the possibility of overnight changes to such easements, there is an increased need to consider how repatriations may be managed. This includes COVID-safe travel arrangements for returning citizens, the safety of staff, and the effective test and trace of those returning home. Facilitating the swift and safe repatriation of people via evacuation flights or ground transport requires multiple state and non-state actors. Significant attention has been given to the amazing efforts of commercial and chartered flights in repatriating citizens, but less focus has been paid to the important role that emergency services can play in supporting repatriation efforts.

In the US, air ambulance teams were deployed to support 39 flights, repatriating over 2,000 individuals. Air ambulance teams were able to supplement flights and reduced over reliance on commercial flights for repatriations (a critique of the UK response[2]). This required monumental effort from emergency service providers. After medical screening or treatment at specific facilities, emergency services (such as police) helped to escort people to their homes to ensure they had accurate public health information and that they understood they should self-isolate.

Authorities should consider how to work with emergency services to develop plans for COVID-19 travel scenarios, to better understand how to capitalise on and protect the capacity and resources of emergency services. Consider how to:

- Develop emergency plans that include a host of emergency service personnel who have technical expertise, and know their communities. Plans should[3]:

- Be trained and practiced

- Regularly incorporate best practices gained from previous lessons learned

- Build capacity in emergency services to support COVID-19 operations through increased staffing and resources

- Anticipate and plan for adequate rest periods for emergency service staff before they go back on call during an emergency period

- Protect emergency service staff. Pay special attention to safe removal and disposal of PPE to avoid contamination, including use of a trained observer[4] / “spotter”[5] who:

- is vigilant in spotting defects in equipment;

- is proactive in identifying upcoming risks;

- follows the provided checklist, but focuses on the big picture;

- is informative, supportive and well-paced in issuing instructions or advice;

- always practices hand hygiene immediately after providing assistance

Consideration can also be given to what happens to repatriated citizens when they arrive in their country of origin. In Victoria (Australia), research determined that 99% of COVID-19 cases since the end of May could be traced to two hotels housing returning travellers in quarantine[6]. Lesson learnt from this case suggest the need to:

- Ensure clear and appropriate advice for any personnel involved in repatriation and subsequent quarantine of citizens

- Ensure training modules for personnel specifically relates to issues of repatriation and subsequent quarantine and is not generalised. Ensure training materials are overseen by experts and are up-to-date

- Strategically use law enforcement (and army personnel) to provide assistance to a locale when mandatory quarantine is required

- Be aware that some citizens being asked to quarantine may have competing priorities such as the need to provide financially.

- Consider how to understand these needs and provide localised assistance to ensure quarantine is not broken

References:

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/649359/EPRS_BRI(2020)649359_EN.pdf

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-53561756

[3] https://ancile.tech/how-to-manage-repatriation-in-a-world-crisis/

[4] https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/ppe-training/trained-observer/observer_01.html

[5] https://www.airmedicaljournal.com/article/S1067-991X(20)30076-6/fulltext

To read this case study in its original format follow the source link below to TMB Issue 21 (p.20-21)

-

Europe,

United Kingdom,

United States of America,

Australia

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b21-wb-21st-september-2020.pdf

Consider rethinking Renewal

Implementing recovery

We describe perspectives on recovery strategy as it has been broadly configured in relation to a variety of crisis events and the effects that recovery has had. We then elaborate on the idea of Repair as an aspect of Renewal that needs to be considered if we are to attend to the shortcomings of recovery. This briefing takes steps towards putting Repair into practice by offering recommendations for its integration into policy.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 21 (p.2-7).

Consider creating a short, engaging video to explain to the public what Recovery and Renewal means in their local area

Local government are producing online materials to help people understand what has happened during response and what is meant by the next phase of COVID-19. This can communicate expectations and align aspirations for what recovery may involve. Consider:

- Producing a short video on how the response effort aims to support people and businesses

- Producing a short video on Recovery and Renewal

- Encouraging widespread dissemination of the video to households, classrooms, offices, waiting rooms, public spaces, social media

- Reach the widest audience by providing the video in different languages

Watch Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council's video: https://www.barnsley.gov.uk/services/health-and-wellbeing/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-covid-19-recovery-plan-for-barnsley/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.barnsley.gov.uk/services/health-and-wellbeing/covid-19-coronavirus-advice-and-guidance/covid-19-recovery-plan-for-barnsley/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTvDF-Z7Rjo

Consider Renewal of local government following COVID-19: Reoganisation, Devolution and Institutional Change in English Government

Legislation

Consider how to manage change for COVID-19 recovery

Crisis planning

Implementing recovery

We propose key considerations for local governments when managing wide-ranging change, such as that induced by a complex, rapid and uncertain events like COVID-19. Identifying and understanding the types of change and the extent to which change can be proactive rather than reactive, can help to support the development of resilience in local authorities and their communities.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 19 (p.2-6).

Consider providing fact-checking services to counter misinformation on COVID-19

There is a glut of information on COVID-19 and more often we are seeing news outlets attempting to check and correct misinformation that be being shared. This should aim to ensure that the public have conclusions about the virus which are substantiated, correct, and without political interference. Myths can be debunked, misinformation corrected, and poor advice challenged. Consider whether to:

- Provide your own fact-checking website

- Contribute to others' fact-checking sources

- Check facts of colleagues and partners to ensure correct information prevails

- Remind others of the importance of not spreading misinformation and checking other peoples' facts

- Link your website to official sources of information so not to promulgate misinformation

-

United States of America

https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2020/03/17/could-that-be-true-sorting-fact-fiction-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.cdhn.org/covid-19-fact-checks

-

United Kingdom

https://fullfact.org/health/coronavirus/

Consider developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response (Part 3): Assessing performance

Crisis planning

Implementing recovery

Part 3: Building on TMB 16 and 17, we present a detailed view of how to assess the performance of the system of resilience before/during/after COVID-19. This briefing presents a comprehensive Annex of aspects against which performance can be considered.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 18 (p.2-7).

Consider how different emergency services have supported COVID-19 response efforts

The all-of society impact of COVID-19 has required many organisations to adapt their operating procedures and deliver alternative activities, including frontline emergency services such as the Police, Fire Brigade, Ambulance and Search and Rescue organisations. We provide examples of first responder adaptation during COVID-19 to demonstrate how frontline services have modified their operations to help tackle the crisis.

Alternative activities undertaken by emergency services

- Supporting health and social care: In California (USA), the National Guard deployed rapid medical strike teams to assist overwhelmed health/nursing facilities[1]. Strike teams involved 8-10 people (e.g. included doctors, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, behavioural health professionals). Strike teams worked across 25 nursing homes – staying on-site for 3-6 days to establish stability of care, disinfected facilities, and staffed mobile COVID-19 testing sites2.

- House-to-house testing: In Guayaquil (Ecuador)municipal taskforces (involving firefighters, medics, and city workers) went house-to-house looking for potential cases[2] . Similarly, in Cambridge (USA), Fire Department paramedics were enlisted to go door-to-door in public housing developments that predominantly housed the elderly and younger disabled tenants to offer Covid-19 tests to residents[3]

- Disinfecting public spaces: In Pune (India) , sanitary workers disinfected and fumigated public areas[4]

- Managing sanitation services: In Ganjam (India), the fire brigade supported the COVID-19 effort by heading the country’s sanitation programme[5]

- Delivering food/medication parcels to vulnerable people: In West Bengal (India), all police stations were made responsible for delivering food and medication to those who are vulnerable and sheltering to avoid food scarcity - the programme was monitored by the State’s District Magistrates and Police Superintendents[6]. In Georgia (USA), a similar scheme involved police officers delivering groceries/medicine to vulnerable people who had placed/paid for orders[7]

- Distributing $100 gift cards: In Smyrna (USA), police handed out $100 gift cards from a community grocery assistance fund to help vulnerable residents purchase essential items[8]

- Counteracting misinformation: In Göttingen (Germany), clashes with tower block residents under enforced lockdown were caused by communication problems between authorities and residents. Translators, working through first responding services, communicated important public health information to relevant residents in German and Romanian via text messaging[9]

Consider the demand for alternative activities from emergency services

To determine how, when and where emergency services can support alternative activities, consider:

- The demand for alternative support:

- Identify current needs where additional capacity to deliver activities is required

- Identify future areas where demand is foreseeable, and where additional capacity may need to be built e.g. through retraining

- How responders can support alternative activities[10]:

- Identify potential capacity in responder organisations, or how this capacity can be created, protected, and prioritised, and how long this capacity may be available[11]

- Obtain strategic-level agreement on the direction, scope and parameters of the alternative activities

- Gather information to understand activities e.g. from partner databases, existing measures, knowledgeable people

- Assess the impact of redeploying staff to other activities and the effects of this on their ability, and the organisation’s ability to cope[12]

- Preparing redeployed resources:

- Identify and source training and safety measures required to redeploy staff to alternative activities (including health and wellbeing of staff and the public)[13]

- Capability of the resources, including:

- Transactional activities i.e. single short-term actions

- Transformational activities i.e. complex, interconnected, longer-term actions needing strategic partnerships

Consider the benefits to the emergency services from delivering alternative activities

The involvement of emergency services in alternative activities has the potential to increase services’ visibility in communities which can help build community trust and engagement[14], reduce misinformation and non-compliance to COVID-19, and bolster local multi-agency partnerships for a more efficient and effective response and recovery[15].

On benefits, consider:

- Working with partners to capitalise on increased contact with marginalised and vulnerable communities e.g. from door-to-door visits. This may include:

- Addressing additional social or health issues, fire safety, safeguarding, or referral to other services

- Community engagement activities and visible street presence through renewing the Neighbourhood Watch Scheme and police Safer Neighbourhood Teams[16]

- Developing joint local/national approaches to provide alternative response to support COVID-19 activities. This may include:

- Emergency services delivering essential items like food and medicines to vulnerable people, driving ambulances, assisting ambulance staff, attending homes of people who have fallen but are not injured[17],[18]

- Increase multi-agency coordination with civil organisations should be central in the design and review measures for COVID-19 response and recovery[19]

- How to capitalise on increased community engagement and volunteerism to help disseminate public health information. Consider working with volunteer and civil society organisations that are close to communities and know their specific needs to:

- Increase capacity for response and recovery considering short and long-term requirements of the need, and of volunteers

- Translate and disseminate timely information in relevant languages and tackle misinformation[20]

- Build relationships in the community to encourage adherence to COVD-19 behaviours, especially with people who have not had previous contact with emergency services

- Enhance community engagement and information sharing to combat misinformation and non-compliance about COVID-19 working with Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships (CDRPs)18

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/ecuador-guayaquil-mayor-

[4] http://cdri.world/casestudy/response_to_covid19_by_pune.pdf

[7] https://cobbcountycourier.com/2020/04/smyrna-police-deliver-food-and-medicine-to-seniors/

[8] https://cobbcountycourier.com/2020/04/smyrna-police-deliver-food-and-medicine-to-seniors/

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-53131941

[11] https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NGA-Memo_Concurrent-Emergencies_FINAL.pdf

[12] https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/strategy/resourcing/transferable-skills-redeploying-during-COVID-19

[15] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25788&LangID=E

[16] https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Policing-a-Pandemic.pdf

[19] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25788&LangID=E

Consider how your policy changes put people and their rights at the centre

Implementing recovery

National Voices, a coalition of English health and social care charities, published its report on 'Five principles for the next phase of the COVID-19 response'. Their five principles seek to ensure that policy changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic meet the needs of people and engage with citizens affected most by the virus and lockdown, especially those with underlying health concerns. They advocate that the future should be more compassionate and equal, with people's rights at its centre. The principles have been developed based on dialogues with hundreds of charities and people living with underlying health conditions. Consider how your policy changes:

- Actively engage with, consult, co-produce, and act on the concerns of those most impacted by policy changes that may profoundly affect their lives

- Make everyone matter, leave no-one behind as all lives, all people, in all circumstances, matter so needs to be weighed up the same in any Government policy

- Confront inequality head-on as, "we're all in the same storm, but we're not all in the same boat" e.g. difference in finances, work/living conditions, personal characteristics

- Recognise people, not categories, by strengthening personalised care and rethinking the category of 'vulnerable' to be more holistic, beyond health-related vulnerabilities

- Value health, care, connection, friendship, and support equally as people need more than medicine, and charities and communities need to be enabled to help

-

United Kingdom

https://www.nationalvoices.org.uk/sites/default/files/public/publications/5_principles_statement_250620.pdf

Developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response (Part 2) - Debriefing using the Viable Systems Model (VSM)

Crisis planning

Consider developing resilient systems for crisis and emergency response

Crisis planning

Part 1: We begin by exploring how the experience of COVID-19 prompts consideration of what national and local (ambitious) renewal of systems to develop resilience to crises and major emergencies could look like. We present a model of 5 systems: operational delivery; coordination; management; intelligence; and policy. This briefing elevates thinking from the performance of individual organisations into considering the performance of the system as a whole.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 16 (p.2-7).

Consider collecting public opinion to understand behavioural, health, and information needs

Tracking public opinion can provide insights into how a society is coping with rapid change, and provides organisations with data that can influence decision-making. During a pandemic this is particularly important as complex information is shared with the public at speed, understanding how this is being understood can help develop evidence-based interventions to support the population. Consider collecting the following types of public opinion information to inform recovery strategies:

- Perceptions of COVID-19 threats to the country, and to individuals

- Use of health services and health seeking behaviours e.g. how comfortable individuals are seeking treatment from hospitals or GPs

- Perceptions of health and care services and how well specific services are managing the pandemic

- Impacts on individuals' sleeping

- Perceptions of local, region or national partnerships e.g. businesses working with local authorities to combat COVID-19

- Impacts of COVID-19 on personal finances, whether positive, negative or neutral

- Perceptions of government performance in dealing with recovery

The population's outlook on getting 'back to normal'

-

United Kingdom

https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2020-04/coronavirus-covid-19-infographic-ipsos-mori.pdf

Consider conducting an impact assessment for you organization to explore the effects of COVID-19, emerging needs or inequalities, and opportunities to improve

Introduction

As local resilience partnerships establish Recovery Coordinating Groups (RCG), this week we talk about impact assessments using details from: HMG Guidance[1], previous briefings (Week 8), and our video[2].

Establish the RCG for COVID-19

When setting up an RCG there are a number of considerations, including:

- the administrative level – the level of the RCG and how it relates to other district/county RCGs

- collaboration – how will strategic partners: align ambitions for partnership-wide recovery/renewal; establish protocols to share information; and agree which activities for each administrative level RCG

- membership – led by local authorities and include organisations with a people, place or economic focus as well as Cat 1 responders

- agree strategic objectives – to support the recovery and renewal of people, place, and processes

Commission an impact assessment

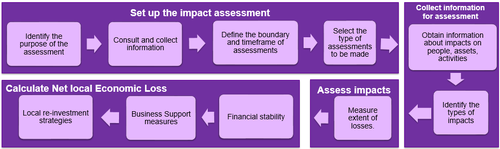

Impact assessments will feed into RCG, either by direct commission or through a strategic coordination group. The assessment will explore the strategic effects of COVID-19, their impacts, specific or emerging system-wide needs or inequalities, and opportunities to improve. National Recovery Guidance1 describes the process of conducting an Impact Assessment as in the graphic:

Collect the consequences

We suggest that the complexity of COVID-19 means the impact assessment should be as strategic and straightforward as possible. RCGs should have strategic-level agreement on the direction, scope and parameters for the impact assessment. Then, strategic information from many sources is needed to fully understand impacts e.g. from partner databases, existing measures, knowledgeable people, surveys, interviews/workshops, or other sources that unlock the impacts on people, place, and processes.

Talking to knowledgeable people should aim to ensure that the assessment does not gather thousands of comments which cloud more than they clarify. A straightforward approach, targeting knowledgeable groups who can support the process, will put more focus on the quality of their insight than on the number of people consulted or number of comments made. For example, consider whether the impact assessment would be better informed if it is more than:

- a single question e.g.: “What significant consequences has COVID-19 had on your area of work?”

- asked to all partners or cell leaders who will consult knowledgeable people as required

- to provide their top 8 consequences on their service delivery to people, place, processes and identify:

- Is it an effect, impact, or opportunity?

- What is its impact rating (e.g. ‘positive, limited, moderate, severe’)?

- Should it be addressed in the short-term or longer-term?

Using this approach, if 15 cells are running then 120-150 significant consequences would be gathered – so to understand these and design corrective actions is a substantial activity. Magnify that ten-fold (in the number of questions, consultees or consequences) and the task becomes unwieldy either collecting overlapping consequences or ones of lower significant.

Analyse the consequences

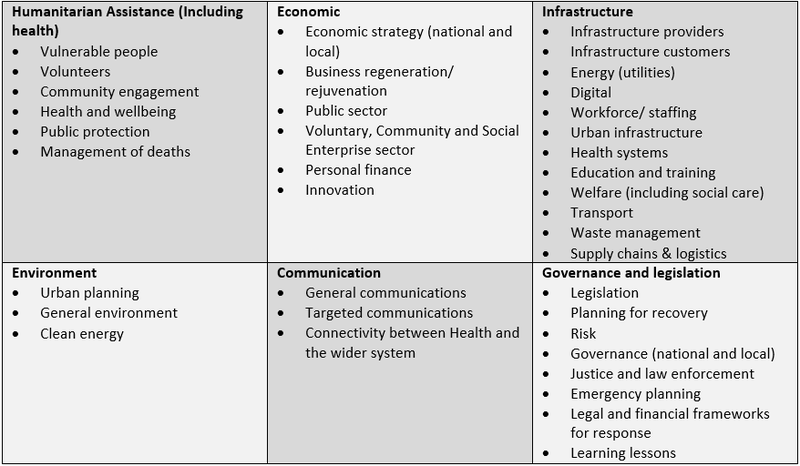

To make sense of the comments, group the comments into the 6 core topics to:

- validate their diversity and broad-based nature;

- identify recurring and complementary topics of significance;

- provide a basis to identify follow-on actions

Within each core topic, grouping comments by the 38 sub-topics (in the graphic) may bring added clarity of what really are the key issues to address.

Understand the rationale

To understand the rationale for addressing core topics, consider the:

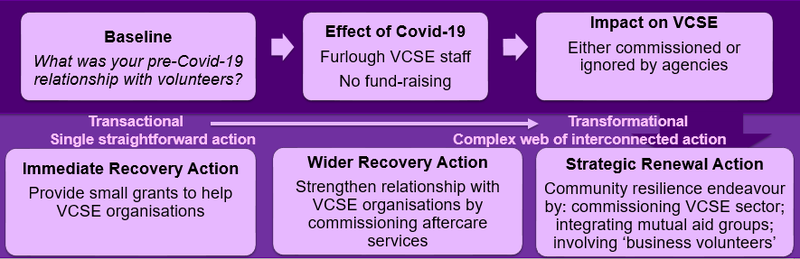

- Baseline – to identify the pre-COVID-19 state of the situation that you are considering changing

- Effect – the immediate consequence of COVID-19 on the baseline

- Impact – the wider/secondary impact of COVID-19 on the baseline/effect

Develop recovery actions

RCG should now be ready to develop recovery actions for significant consequences. Actions may be:

- Transactional – a single, straightforward, short-term action by an organisation

- Transformational – a longer-term portfolio of action by a strategic partnership of organisations to deliver a complex web of interconnected, democratically significant, renewal activity

Actions can be at three levels of comprehensiveness depending on scale and timing:

- Immediate Recovery Action – an organisation delivering a transactional action to address an effect

- Wider Recovery Action – a partnership delivering a series of transactional actions to address an effect

- Strategic Renewal Action – a partnership delivering transformational actions to address a strategic impact or opportunity

Understanding the baseline, can identify effects and impacts. These can be addressed with immediate, wider or strategic actions depending on the desired scale, motivation, and funding available, as in the graphic.

Deliver recovery actions

RCG must decide the priority for each action by evaluating its likelihood, effort, motivation, capability, capacity, duration, and resources needed, and its impact on reputation from (not) pursuing it.

For more details contact: duncan.shaw-2@manchester.ac.uk & david.powell@manchester.ac.uk

References:

[1] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/national-recovery-guidance

[2] Video on ‘Planning Recovery and Renewal’ www.ambs.ac.uk/covidrecovery

Consider policing during the COVID-19 pandemic

We discuss enforced lockdowns and restrictions on movements, combined with challenges posed by public demonstrations and protests which resulted in police needing to navigate complex and dynamic relationships with the communities they serve. This briefing provides reflections from the USA and Australia on policing to enforce local lockdowns, and manage civil unrest during COVID-19.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TBM Issue 15 (p.2-8).

Consider assessing your organisation's plan for responding to COVID-19 outbreaks

To plan for local outbreaks of the pandemic, local government in England were required to develop and publicise their Local Outbreak Plan on how they will manage any sporadic surges of the virus in their local area. To structure these outbreak control plans, UK public health authorities identified seven connected themes to cover: care homes and schools; high risk places and communities; methods for local mobile testing units; contact tracing and infection control in complex settings; integrating local and national data; supporting vulnerable people to self-isolate; establishing governance structures. Other countries (e.g. Ireland and New Zealand) have also required the development of outbreak control plans, especially for outbreaks in care homes.Consider how to:

- Review how other organisations have planned for outbreaks and learn from the contents of those plans

- Develop an outbreak control plan for how to manage a spike in COVID-19 case

- Use others' plans to confirm the contents of your plans and/or expand those contents

- How to exercise those plans and how to share the learning from those exercises with other organisations

- Developing bespoke outbreak control plans for specific sectors e.g. care homes

-

United Kingdom

https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/16599/covid_19_local_outbreak_control_plan_birmingham

-

United Kingdom

https://www.northyorks.gov.uk/our-outbreak-plan

Consider what information to provide to international travellers before they leave your country, how they can travel safely and arrive into the destination country and what they should do after entering your country

As countries begin to open their border to international travel, there is much to consider, not least the information provided to travellers before they leave your country, as they travel, and as they enter your country.

Information provided to travellers before they leave their country is key, so travellers can prepare themselves to travel to an overseas destination with the right supplies and knowing the expected behaviours. This is especially important during COVID-19 where countries have differing regulations regarding social distancing, travel within the country, and fines. Consider providing a government-issued 'safer travel information sheet' and advising travellers to download it before they leave the country. The information sheet could cover:

- Travel advisory for the country they are to visit

- Behaviours and supplies needed for COVID safe travel and at the destination e.g. face masks

- How to travel safely on all legs of the trip (from home to final destination) e.g. not arriving too early at departure points, ticketing, parking

- Expectations for safe travel practices such as social distancing, required face coverings and when/how to wear masks

- Tips for travelling using all types of transport e.g. cars, aircraft, ferries

- Exemptions for people e.g. who does not need to wear a face covering

- Where to find more information, key contacts and their contact information

The travel industry has a central role in advising travellers of travel-related and destination-specific COVID-19 information. The travel industry can provide advice to:

- Prepare travellers for practical departure and arrival procedures e.g. temperature sensors, health declaration forms

- Practice COVID-19 behaviours whilst travelling e.g. mask wearing, personal interactions, expectations on children and infirm

- Provide up to date information to travellers on the COVID-19 situation in the arrival country and how to access current information during their stay

- Identify what travellers should do if they suspect they have symptoms during their stay and before they travel home

- Inform travellers of mandatory acts on arrival, such as registering or downloading a mandated track and trace phone app

- Educate travellers on the local expectation for behaving safely in the country and local means of enforcement

- Detail what travellers should do on arrival e.g. quarantine, self-isolation, in the case of a local lockdown

- Where to find more information, key contacts and their contact information

- Penalties for non-compliance with local requirements for COVID-19

When travellers land in a different country, or even return to their home country, they may not have updated information or knowledge about COVID-19 transmission, or the local expectations or regulations put in place to encourage safe behaviours. Instead travellers may have COVID-19 practices that do not align with the expectations of the country they are in, so need information to make adjustments so they can live by the county's current protocols and legislation. So that travellers arriving into your country are able to act according to local advice, consider how to update travellers on practices they should follow, covering:

- Major local developments on the virus

- The impact of those developments on new behaviours, expectations, curfews, etc.

- Information on the sorts of services that are available, including holiday-related and travel

- Information on regulations, behaviours, practices and expectations e.g. quarantine, self-isolation, track and trace

- Information on residence permits and visas procedures

- Information on onward travel, transiting through the country and returning home

- Where to find more information, key contacts and their contact information

Appropriate channels should be considered to share this information with travellers e.g. travel providers, travel infrastructure providers, hotels.

To read this case study in its original format (including references), follow the source link below to TMB Issue 14 p.15-16.

Consider how to develop strategies for Recovery and Renewal

We have produced a video on how local authorities can begin processes for recovery and renewal: https://bit.ly/2BORO2e. It outlines how resilience partnerships can develop recovery strategies and ambitious plans for renewal of their areas. It covers how to:

- establish the basics of Recovery

- set up a Recovery Coordinating Group

- assess impacts from COVID-19

- implement recovery strategies

-

United Kingdom

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/research/recovery-renewal-resilience-from-covid-19/

Consider how to effectively implement local or 'smart lockdowns'

Recently, European Union countries have begun enforced lockdowns in smaller regions in response to new outbreaks of COVID-19, rather than bringing the entire country to a halt. 'Smart lockdowns' have been undertaken in Germany, Portugal, Italy, and the UK where local governments have declared local lockdown where cases of COVID-19 could not be contained.

Special consideration should be given to the identified causes of spikes in transmission. Localised COVID-19 outbreaks in Europe and the USA share a number of similarities. In most cases, overcrowded living conditions, poor working conditions, cultural practices, and/or limited socio-economic capital point to increased risk of infection and transmission. In Warendorf (Germany) and Cleckheaton (England), outbreaks were attributed to abattoirs and meat factories , which often employ migrant workers in poor working conditions on low-paid contracts. While the outbreak in Cleckheaton does not seem to have spread into the community, the fallout from the abattoir in Germany resulted in the lockdown of the city of Warendorf. Similar patterns are being witnessed in the USA, where workers from meat processing plants in Georgia, Arkansas and Mississippi, who are predominantly migrant workers or people of colour, have died from the virus or have become infected.

Conversely, in Marche (Italy) and Lisbon (Portugal) outbreaks originated in migrant communities that were living in overcrowded quarters or experiencing unsafe working conditions. Similarly, this week in Leicester (England), a local lockdown has been enforced. Possible reasons for the spike in cases shares stark similarities to the local lockdowns that have gone on elsewhere.

Reportedly, in Leicester some garment factories continued to operate throughout the crisis and forced their workers to work despite high levels of infection. Wage exploitation of the largely immigrant workforce, failure to protect workers' rights in Leicester's garment factories (a subject of concern for years), and poor communication of lockdown rules with Leicester's large ethnic minority community have all contributed to a resurgence in the disease.

Secondly, the East of the city, suspected to be the epicenter of the outbreak, has extreme levels of poverty, is densely packed with terraced housing, and has a high proportion of ethnic minority families where multi-generational living is common.

These patterns barely differ from the spike in cases in Singapore in May 2020 in which Singapore's progress on tackling COVID-19 was halted as tens of thousands of migrant workers contracted the disease due to poor living conditions and being neglected by testing schemes as their migrant status and relative poverty meant they were overlooked by the government.

Implementing smart lockdowns requires:

- Outbreak control plans for the COVID-19 partnership to be developed, written, and communicated to wider partners, specifying their role in the outbreak response

- Collaborate closely across the public sector to understand possible at-risk communities e.g. minority groups, migrant workers, those in poor or insecure housing, those in particular occupations

- Identify new cases early through rapid testing and contact tracing and sharing timely data across agencies

- Decide the threshold at which a cluster of new cases become an outbreak

- Decide the threshold at which an outbreak triggers the lockdown of an area, and how the size of that area is determined

- Collaborate closely with the public sector to communicate and enforce local lockdowns e.g. the police, the health and social sector, local leaders

- Ensure there is capacity in local-health care systems to respond to the outbreak

- Collaborate with citizens to ensure good behavioural practices are understood and adhered to e.g. hand washing, social distancing at work and in public areas

- Ensure the parameters of the local lockdown are clear. For example, in a UK "local authority boundaries can run down the middle of a street" which makes it different to differentiate what is appropriate for a city or region, and to understand how a local community identifies with the place and boundaries in which they live

Local outbreaks, whether in migrant worker accommodation, meat factories or impoverished areas of a city, clearly underscore the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on minority, migrant, and poor communities. Increased engagement with, and attention to ethnic minority groups, marginalised people and impoverished communities is key to staving off local and national resurgences of COVID-19. Strong multi-organisational partnerships are required to account for varying needs and concerns with certain communities including addressing their living and working conditions and the risks this poses to public health.

To read this case study in its original format (including source links and references, follow the source link below.

-

United Kingdom,

Italy,

Germany,

Portugal

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/media/ambs/content-assets/documents/news/the-manchester-briefing-on-covid-19-b13-wb-29th-june-2020.pdf

Consider using international lessons gathered through TMB as a means to ‘sense check’ strategies for recovery and renewal

View all issues of The Manchester Briefing: https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/research/recovery-renewal-resilience-from-covid-19/briefings/

-

United Kingdom

https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/research/recovery-renewal-resilience-from-covid-19/

Consider how to ensure communication and connectedness in rural communities

Isolation and loneliness is a big issue in rural communities which has been heightened by lockdown. Consider projects such as ConnecTED Together that offer:

- A phone befriending service

- Signposting to other agencies

- Fortnightly packs that are emailed featuring news, reviews, quizzes, short stories, and recipes

- A dedicated YouTube channel with video features on themes such as exercise, healthy eating and working with technology

- 'How to' guides e.g. use of digital devices

Campaigns that include the KnitTED Together campaign where people can share pictures of creative knitting and experiences via social media

Consider Ambition for Renewal

Implementing recovery

We consider here Recovery and Renewal and explore how recovery actions relate to the concept of Renewal, which we have discussed in previous weeks of The Manchester Briefing. We also consider the extent to which recovery actions will extend into renewal, and whether they may fizzle out as fatigue as other priorities, such as Brexit, close in.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 11 (p.2-7).

Consider how local government can support businesses to develop business continuity (BC) plans

Consider using the Emergency Planning College Business Continuity (BC) checklist to understand how well BC is incorporated into core areas such as risk management (see BS65000 for further examples). The checklist provides signposting to relevant guidance. Example guidance includes:

Roles, responsibilities and competencies

- Identify BC roles and command and control structures e.g. strategic leads; BC advisor/coordinator; incident management etc

- Promote effective leadership (e.g. ISO22301; ISO22330)

- Document information including plans, procedures, roles and competencies, and the recording of decisions, actions and rationale (e.g. ISO22301: Clause 7.5)

Monitoring and evaluation and decision making

- Effectively monitor impacts and use of trusted, key guidance for BC to inform decisions

- Agree decision-making methodology and governance structures for BC

- Use models such as the Joint Decision Model (JDM) for making decisions for multi-agency response or organisational level

- Agree processes for effectively standing response down, including decision makers and deciding factors (e.g. ISO22301: Clause 8.4.4.3)

Recovery of businesses and Maintenance of BC

- Promote recovery as a chance for innovation of current processes, organizations, communities and behaviours, which is in keeping with 'Continual Improvement' (e.g. ISO22301: Clause 10.2; 'Innovation' in BS65000)

- Advocate the lifecycle of the BC plan and the accuracy of priorities and how lessons are learned from incidents

-

United Kingdom

https://www.epcresilience.com/EPC.Web/media/documents/Tools%20and%20Templates/20200421-EPC-BC-Checklist-NEW.pdf

Consider developing Recovery Actions for COVID-19

Crisis planning

This briefing builds on The Manchester Briefing (TMB) 8 to discuss more about the effects and impacts of, and opportunities arising from, COVID-19; what these mean for developing recovery strategies and for Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) which plan the response to crisis.

Follow the source link below to TMB Issue 9 to read this briefing in full (p.2-10).

Consider the different areas for which an Impact Assessment of COVID-19 response and recovery strategies could be commissioned

Consider how to start recovery and renewal (and Impact Assessments)

Implementing recovery

This briefing outlines the key issues that should be considered by all partners in the initial stages of planning recovery and renewal, those which should be addressed prior to commissioning Impact Assessments. The briefing concludes by highlighting the need for RCGs to align with other local strategic partnerships to enable recovery and renewal, taking into consideration the breadth of effects, impacts and opportunities from COVID-19.

Follow the source link below to read this briefing in full (p.2-7)

Consider the criteria used to ease lockdown restrictions

In the UK, five tests must be met:

- Protect the healthcare system and its ability to cope so it can continue to provide critical care and specialist treatment

- The daily death rates from coronavirus must come down

- Reliable data must show the rate of infection is decreasing to manageable levels

- Have confident that testing capacity and PPE are being managed, with supply able to meet not just today's demand, but future demand

- Have confidence that any changes made not risk a second peak of infections

Five alert levels are developed to guide the level of lockdown restrictions.

-

United Kingdom

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-10-may-2020

Consider how to encourage evidence-based media policies around pandemic reporting

Including:

- Clearly identify authoritative sources

- Encourage social media companies to correct disinformation

- Develop policies on media use of traumatic footage

- Mitigate individuals' risk of misinformation

- Improve health literacy and critical thinking skills

- Minimise sharing of misinformation through fact checking

Consider the criteria used to ease lockdown restrictions.

Consider a 'traffic light' approach to communicate the exit plan to the public

This is a plan that will explain what is permitted and prohibited at each phase of easing the lockdown. The first phase would deliberately be called red, to ensure people stopped to think before they did things:

The red phase

- Some shops could re-open with strict social distancing, as most supermarkets do now

- Many shops might choose not to re-open for commercial reasons e.g. as demand would be low

- Travel should be discouraged and many international flights banned

The amber phase

- Over-65s should live as if under a hard lockdown

- Daily new cases <500 persons, Testing capacity >100k, Tracing capacity >50%, Shielding

- Work if your workplace is open and if you have a 'clear' reading on your contact tracing app. Use masks where possible. Otherwise only leave home as for Hard Lockdown

- Unlimited private car journeys allowed, although people are discouraged from crowded destinations

- Vary the rush hour with different opening and closing times to minimise pressure on public transport and reduce crowds

- Patrons encouraged to show a 'clear' reading on your contact tracing app. Must follow social distancing

- Wear masks and gloves when using public transport

- Restaurants could reopen but with strict seating demarcations to uphold social distancing

- Smaller shops could reopen

The green phase

- Daily new cases <100. Testing + tracing in place. Public gatherings <100 allowed

- Sporting events or mass gatherings could take place, and places of worship can reopen

- Mass transit could return to normal

- The return of international flights should be based on the risks of flying to other countries

- Macro-economic policies such as cutting VAT rates might be employed to boost spending

-

United Kingdom

https://institute.global/policy/sustainable-exit-strategy-managing-uncertainty-minimising-harm

Consider sending personalised letters to children of keyworkers

Children across Northampton, UK who had a parent that worked in the local police force, received a letter from the Chief Constable. The letter:

- Thanked children for 'sharing their parents' and for the child 'being part of the team'

- Thanked children for washing their hands properly, doing their school work and only going for one walk a day, making it possible for their parents to work

Consider risk assessments to examine the requirements for the options for easing lockdown whilst supressing the spread of COVID-19

Lockdown could be eased through:

- Gradual school reopening because children are at low risk, and there are high economic and educational costs to school closure

- Gradual return to work with younger people first (age segmentation) as they are relatively less at risk of COVID-19 than older people

- Gradual return to work by sector/workplace (sector segmentation) as some pose less risky than others

- Gradual release of lockdown by geography (geographic segmentation) as COVID-19 cases and NHS capacity vary across regions

Consider risk assessments for each of these options, since there are challenges with each e.g. cross-sector supply chains limit the benefits of sector segmentation.

Consider the following factors in the assessment:

- Costs vs. benefits

- How quickly can it be done?

- Will it be seen as fair?

- How practical is it?

- Can it be enforced?

-

United Kingdom,

India

https://institute.global/sites/default/files/inline-files/A%20Sustainable%20Exit%20Strategy%2C%20Managing%20Uncertainty%2C%20Minimising%20Harm.pdf

Consider working in partnership for recovery and renewal

Implementing recovery

This briefing shares our early thinking on recovery and renewal, and the opportunities COVID-19 has offered. We identify the opportunity to recover and renew how power and partnerships support working across five groups: national, local partnerships, organisations, local communities, and people. We call for the need to think about people, place, and, processes which have to recover and renew.

To read this briefing in full, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 4 p.2-6

Consider disseminating free standards that provide frameworks for recovery

Such as ISO22301 'Business continuity management systems' from The British Standards Institution (BSI).

Guidance such as this addresses 'financial, legal, regulatory, environmental, reputational and emotional consequences arising from a risk or actual incident, and the consequences of activities associated with organizational recovery'. It also acknowledges the importance of flexible and scalable recovery in times of uncertainty.

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/topics/novel-coronavirus-covid-19/risk-management-and-business-continuity/

Consider sharing good news stories

This can reflect different experiences of the crisis and its effect on our lives which are more uplifting and positive. Volunteers can help with this, as can the voluntary sector. Check out the "Together Cumbria" social media accounts which are run by voluntary organisations on behalf of the resilience partnership.

Consider the creation of a one-stop database for information in real-time

This can include the number of infected people, their status, characteristics (e.g. age, gender), number of inquiries to the call centre, number of people using subways, etc. The city can also provide the website's source code as open-data, so that other municipalities and institutions can use the data and replicate similar webpages.

Consider working through community programmes to tackle the 'infodemic'

Local government plays a key role in building trust in new measures and tackling misinformation. There may be a need for this in the UK. Of 2,250 adults surveyed:

- 15% of people thought seasonal flu was deadlier than coronavirus

- 31% believed "most people" in the UK had already had the virus without realising it

- 39% think they should be shopping "little and often to avoid long queues", when the advice is only to go out to shop for basic necessities and as infrequently as possible.

- 25% believed the conspiracy theory that coronavirus was "probably created in a lab" - one of several conspiracy theories currently circulating on social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube.

Surveys like this help your organisation identify areas where their messaging is not as clear as it needs to be. Local government would benefit from continuing surveys on public opinion.

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/uk-52228169

Consider a framework for impact for recovery

Planning for recovery

Implementing recovery

In this briefing, we present an initial framework to assess the impact of COVID-19, building upon the UK Government’s National Recovery Guidance and Emergency Response and Recovery Guidance. This framework provides the structure to document national/international early recovery lessons for COVID-19 in The Manchester Briefing.

The framework asks you to consider types of impact, and how you can address each to enable recovery to take place. To view this framework, follow the source link below to TMB Issue 1 (p.7).

Consider analysing the impact of COVID-19 on all aspects of cities

Local government should analyse the impact of Covid-19 on all aspects of their cities. These should be formed as impact assessments that analyse:

- Local Community Impacts (from national guidance)

- Humanitarian Impact Assessment (from ERF Humanitarian Assistance Plan)

- Equality Impact Assessments

- Multi-agency impact analysis

-

United Kingdom

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/national-recovery-guidance

Consider appointing senior officers to Recovery Coordination Groups

Local government should assign appropriate senior officers and other knowledgeable parties to the Recovery Coordination Group. These staff will plan recovery by designing and implementing aspects of recovery and decide how this can be done more effectively for the recovery of all of society. Key roles in the Recovery Coordination Group includes:

- Strategic Lead

- Tactical Lead

- Secretariat/Programme Management Officer

- Functional representatives: Appropriate staff from relevant sectors

Reference: Essex County Council-Emergency Planning & Resilience, UK

Consider appointing the Recovery Coordination Group to develop a wide-ranging recovery strategy and action plan

Local government should ask the Recovery Co-ordination Group to develop a wide-ranging recovery strategy and action plan, focussing on short, medium and long term activities. This group should include governance arrangements and sub-groups to address particular aspects of recovery and should plan for the transition between response and recovery phases of Covid-19.

Reference: Essex County Council-Emergency Planning & Resilience, UK

Consider collecting stakeholder and community feedback on actions and service delivery

Local government should collect stakeholder and community feedback on actions and their delivery. This will monitor and evaluate strategies to ensure stakeholders' needs are being met and that actions are having the desired impacts.

Reference: Essex County Council-Emergency Planning & Resilience

Consider disseminating free international standards to enhance community recovery

Local government should support community recovery by disseminating free international standards to enhance community recovery. The British Standards Institution (BSI) has made the following standards available for free to planners:

- BS ISO 22319:2017 Community resilience - Guidelines for planning the involvement of spontaneous volunteers

- BS ISO 22330:2018 Guidelines for people aspects of business continuity

- BS ISO 22395:2018 Community resilience. Guidelines for supporting vulnerable persons in an emergency

- BS ISO 22320:2018 Emergency management. Guidelines for incident management

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/topics/novel-coronavirus-covid-19/risk-management-and-business-continuity-covid-19/

Consider disseminating free international standards to the business community

Local government should support business recovery by disseminating free international standards to the business community. BSI has made the following standards available for free to businesses:

- PD CEN/TS 17091:2018 Crisis management: Building a strategic capability

- BS EN ISO 22301:2019 Business continuity management systems - Requirements

- BS EN ISO 22313:2020 Business continuity management systems. Guidance on the use of ISO 22301

- ISO/TS 22318:2015 Guidelines for supply chain continuity

- ISO 22316:2017 Organizational resilience. Principles and attributes

- Risk Management

- BS ISO 31000:2018 Risk management - Guidelines

- BS 31100:2011 Risk management - Code of practice and guidance for the implementation of BS ISO 31000

-

United Kingdom

https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/topics/novel-coronavirus-covid-19/risk-management-and-business-continuity-covid-19/

Consider including public health and other local actors in Recovery Coordination Groups

Local government should strengthen and support public health systems by ensuring representation of all sectors on the Recovery Coordination Group. The Recovery Coordination Group should take multiple actions simultaneously to ensure swift progress on recovery is made.

-

United Kingdom

https://4sd.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/200325-Narrative-Eleven-Non-health-Dimensions-of-the-COVID-19-Emergency.pdf

Consider promoting empathy in the Recovery Coordination Group

Local government should ensure empathy is prominent in the Recovery Coordination Group including in all strategic decision making and activities and the application of 'Principles of Resilience' to provide an all-of-society approach that considers need and their circumstance.

Reference: Essex County Council-Emergency Planning & Resilience, UK